Written by Jaelyn Molyneux, BA’05

Dr. Geoffrey Hay, PhD, came home one day to find his new energy-efficient house — cold. He wanted to know where it was happening, why it was happening and what to do about it. Most of all, he wanted to see what was happening by making that heat loss visible, colourful even, with an image that showed red for hot and blue for cold.

“If you can’t see it, you can’t do anything about it,” says Hay, BSc’91, a geography professor at the University of Calgary. Worse yet, if you can’t see something does it even exist?

In terms of heat loss in homes, the answer is a resounding yes and there are huge opportunities to be more energy-efficient. If only we knew where to look and what to do.

Hay says approximately 50 per cent of the energy produced around the world is for buildings, including residential houses. In Canada, households consumed 1.4 million terajoules of energy in 2019. Alberta, where natural gas is the main source of energy, had the highest consumption with a household average at 124.6 gigajoules.

On average, a home loses 30 to 50 per cent of its energy. It escapes through roofs, walls, windows and more. That’s not great for the environment. All that wasted energy is energy that didn’t have to be produced, or it could have been used elsewhere. And that loss results in hundreds of millions of dollars spent on household energy bills for something that is never used.

“It turns out the least-expensive energy is not solar. It’s not wind. The least-expensive energy is energy efficiency,” says Hay. “It’s cheaper to save energy than it is to produce it.”

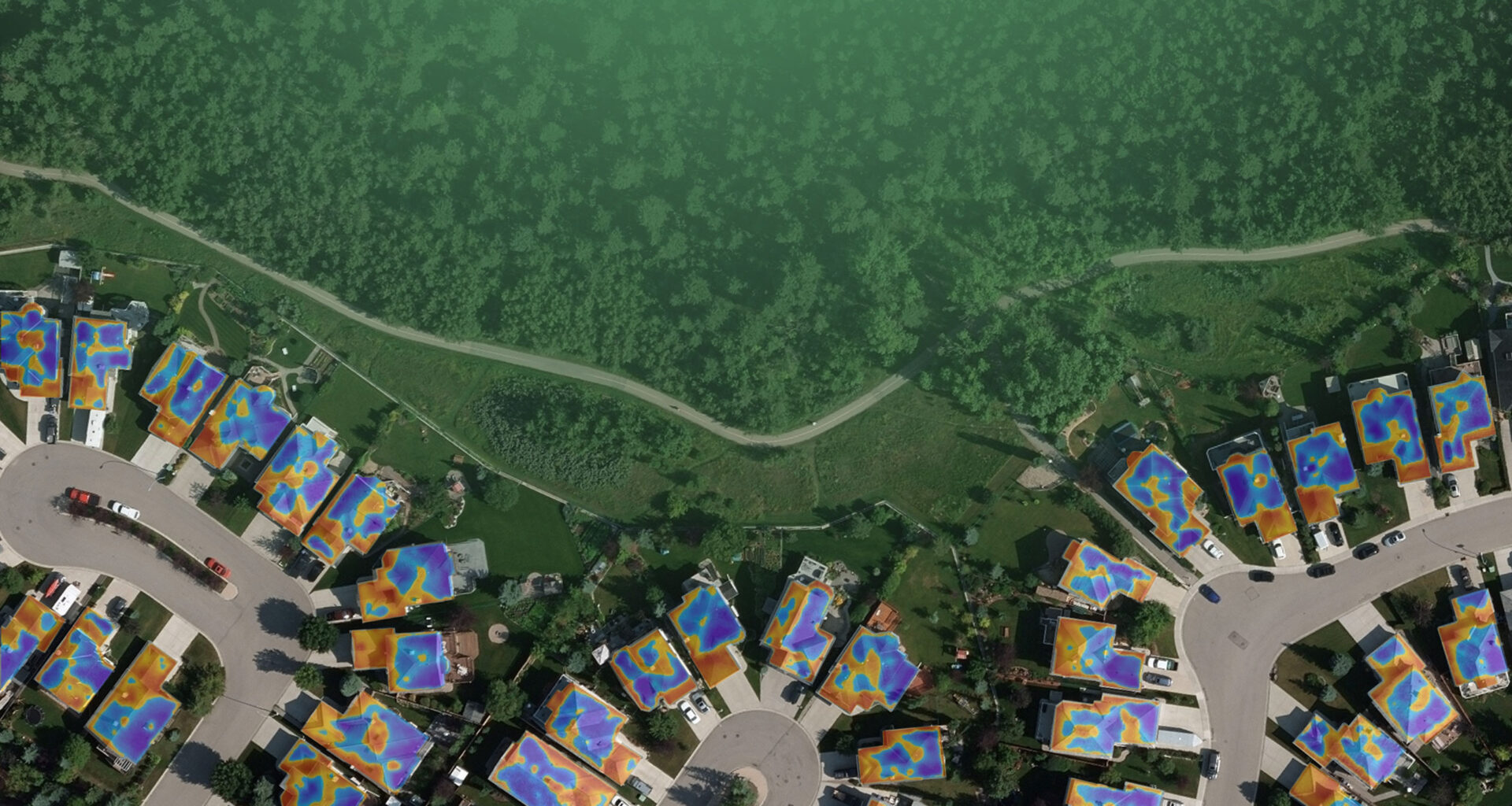

Using his skills as a geographic information scientist, Hay took his colour-coded heat-loss image idea further. Gradients of reds and blues would be created using geo-intelligence and connect to locations including doors, windows, chimneys, or roofs. In Hay’s own home, he saw the garage and front vestibule were where the heat was escaping and that was where he had to make improvements.

Using Hay’s system, these leaky locations would be linked to local service providers, and organizations providing energy retrofit grants and green products with public ratings about the quality of the products and services, indicating the amount of energy leaving every building. Heat-loss information could be compiled at the building, community and municipal level. That would enable competition between cities, show improvements over time, or simply be used to locate where the wasted heat is happening and verify that a retrofit has been correctly implemented.

That idea became the UC Heat Energy Assessment Technologies (HEAT) research program. HEAT uses an aircraft equipped with a specially cooled, Canadian-made thermal camera that collects heat-loss information taken by methodically flying over and examining neighbourhood rooftops. It goes out at night when the heat from the sun isn’t a factor. Its sensors can pinpoint to within 25 centimetres where heat is being lost and can measure temperature to within 0.05°C. The data is corrected for microclimate, elevation, building materials and geometry to get precise results.

In 2013, HEAT won the MIT CoLab Grand Prize, beating out 400 other entries. Cities and companies from around the world came calling. By 2014, MyHEAT Inc. was created as a commercial startup, with its headquarters in Calgary. Today, its 28 employees work with energy suppliers, municipalities and builders that use the MyHEAT platform to connect customers with services to measure and improve energy efficiency in their homes. A decade in, MyHEAT has so far heat-mapped five million homes, serving more than 20 million people in more than 50 cities across North America.

While the company continues to work on commercial products and hone the user experience, Hay focuses on new ideas, serving on the MyHEAT board as its chief science officer. Under his supervision, UCalgary graduate students work with MyHEAT on projects that push the platform and its applications, develop new ideas and keep up with continued advancements in machine learning, energy efficiency and emerging technologies.

“I love innovating and solving problems,” says Hay.