Written by Valerie Fortney, BA’86

Hunger. It’s a sensation all living beings know — the feeling of discomfort or weakness brought on by a lack of food, quickly followed by a compelling desire to eat. For most of us, this unnerving sensation is readily sated with a meal at home or on-the-go. Yet the problem of hunger is a growing one right here in Canada and has far-reaching effects, from impacting physical and mental health and relationships, to hurting the ability to find and keep a job.

While there is certainly more than enough food produced to feed the global population, more than 690 million people go hungry every day — and that number is on the rise. By the year 2030, it’s estimated that the number of people affected by hunger will surpass 840 million, more than 10 per cent of the world’s population.

In recent years, this urgent global issue has been described as “food insecurity.” This is defined as inadequate or insecure access to food, mostly due to financial constraints. While the term may have a more technical ring to it than “hunger,” its devastating effects are just as real. In 2017-18, according to Statistics Canada, one in eight Canadian households, or about 4.4 million people, were food-insecure, and one in 16 Canadian children suffer from food insecurity, which can be anything from the fear of running out of food to going days without eating.

Most people who suffer from food insecurity are in the workforce, but low wages and job-precariousness mean that even those able to work often don’t bring in enough income to avoid its effects. According to a report from the non-profit Community Food Centres Canada (CFCC), during the COVID-19 pandemic the number of Canadians experiencing food insecurity has increased by a staggering 39 per cent, disproportionately impacting Black, Indigenous and northern communities. Along with low wages and employment insecurity, low social assistance rates, systemic racism and the high cost of food in Canada’s north are among the reasons cited.

The eradication of food insecurity, however, is being tackled on a wide variety of fronts, with the understanding that it requires the co-operation and integration of policy actions across social, health, economic and agricultural domains, as well as all three levels of government.

With food supply chains temporarily impacted during the pandemic and predictions of more pandemics to come, there is also an increasingly urgent need to re-evaluate where and how we get our food — and how sustainable these practices will be in the coming decades.

In recent years, UCalgary has played a leading role in promoting healthy living and safe food for Canadians, with projects undertaken by academics, employees and alumni that address food insecurity in innovative ways. Initiatives like UCalgary’s Simon Farm Project also address the issue with sustainability at its core, ensuring that ecological balance and the avoidance of depleting natural resources are also incorporated into the aims to alleviate food insecurity for all.

UCalgary researchers, alumni and staff are working to address the urgent need to fight food insecurity in our communities, whether for urban and rural families or for residents of remote northern communities. While these passionate individuals and groups address the issue in unique ways, they share a common belief: that hunger has no place in a healthy and caring society.

The Calgary Community Fridge

908 Centre St. N., Calgary, AB

It’s the centrepiece of any home, the big appliance teenagers run to at the end of the school day, the destination for grumbling tummies and creative cooks. For far too many, though, the family fridge brings more anxiety than relief, its bare shelves a stark reminder of the tangible impact of living with food insecurity.

So, when photographs of brightly painted fridges started popping up on Sasha Lavoie’s Instagram feed earlier this year, it got her thinking about how this symbol of plenty — and, far too often, privilege — is far from universal.

“It really struck a chord with me,” says Lavoie, BA’12, communications co-ordinator for UCalgary’s Campus Mental Health Strategy and current undergraduate student in the Department of Psychology. “They were vibrant fridges, their opened doors showing fresh, colourful vegetables and fruits.” These weren’t just garden-variety Instagram posts of a ubiquitous household appliance, though; what Lavoie had discovered was the “community fridge,” part of a growing North America-wide movement to ensure easier access to healthy food for all.

The fridges are appearing on well-travelled streets, often tucked in between a local pharmacy or coffee shop and other businesses. They are stocked and replenished, often every day, with healthy, fresh, donated food for the taking — no questions asked.

Lavoie says she and a small group of like-minded friends saw an opportunity to do something concrete in their own city in a time of extreme deprivation for many due to the global pandemic. “Community involvement and lowering barriers to accessing aid resonate so much for me,” she says. The project appealed to her as — in the words of fellow organizers — a “mutual-aid project,” wherein individuals take charge of caring for one another through a redistribution of wealth and resources.

The Calgary Community Fridge, located outdoors at 908 Centre St. N. and protected from the elements in an open shed, is accessible 24/7 and stocked by local restaurants, grocers, businesses and residents; it is regularly cleaned and restocked by a small team of volunteers.

Lavoie, a native Calgarian, says her experiences volunteering with agencies such as Distress Centre Calgary opened her eyes to the close connection between mental health issues and food insecurity.

“Seeing the end of a food hamper or even accessing one is a real stressor,” she says. “In an ideal world, we wouldn’t need community fridges — this is just one more way to help our neighbours.”

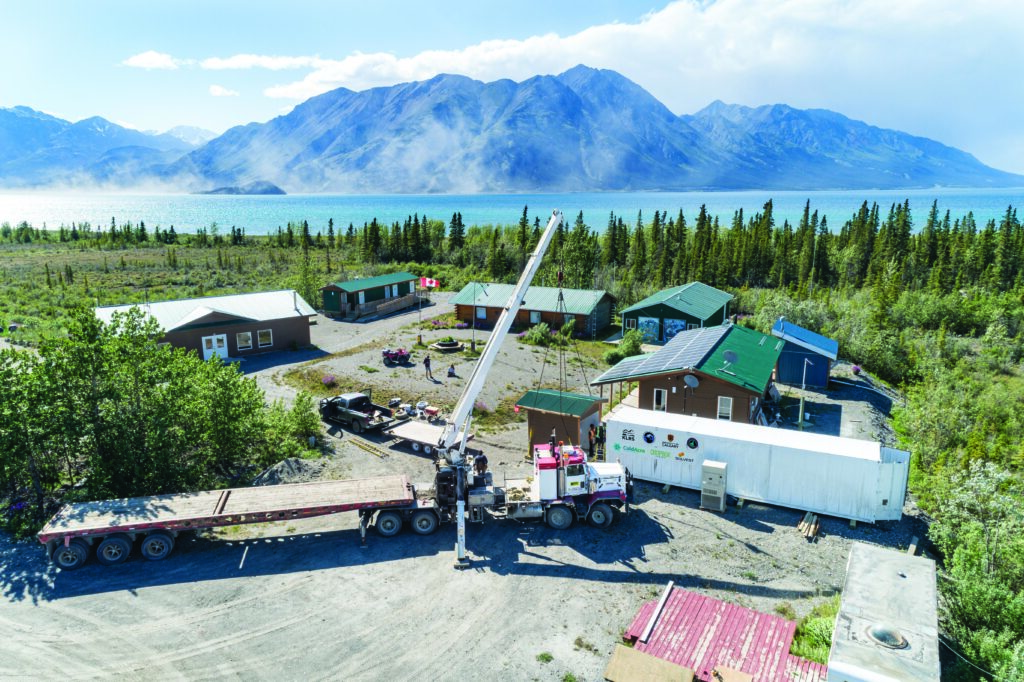

Arctic Institute of North America

University of Calgary

Kluane Lake, Yukon

It’s a place of breathtaking beauty, where giant glaciers are surrounded by majestic mountains and ancient icefields. The starkness of the landscape is matched only by its extreme seasons: eternal sunshine in the summer; weeks of darkness and temperatures plunging to -40°C in winter.

The often unforgiving land and climate of the Kluane region of Canada’s Yukon territory also presents some big challenges for those who call it home. A short growing season, combined with a variety of social, economic and political forces, have led to the Yukon having some of the highest rates of food insecurity in the country.

A new initiative, launched by UCalgary’s Arctic Institute of North America, is intended to play a role in addressing this inequity. Researchers at the Kluane Lake Research Station (KLRS), located 220 kilometres northwest of Whitehorse, recently began planting their first crops combining two technologies — a hydroponic system called Cropbox from the United States, along with clean, solar-powered energy courtesy of Yukon-based Solvest Inc. and Cold Acre Food Systems Inc.

“Our goal is to essentially demonstrate these units can operate 12 months of the year,” says Dr. Henry Penn, PhD, of the hydroponic system, a 40-foot shipping container that is the equivalent of a traditional growing acre. Penn, a post-doctoral researcher with the Institute, says that for people living in the region, access to fresh produce often requires a several-hour drive to Whitehorse, where grocery store prices for such essentials as apples and potatoes can be two to three times higher than in southern centres like Calgary.

The project’s birth was the result of a conversation Penn had with Solvest and Cold Acre about using solar technology to power the research station, which, for more than a half-century, has been conducting research in a wide variety of disciplines, from glaciology and botany to zoology and anthropology. Solvest was also looking to try hydroponic growing, which has seen success in such centres as Whitehorse. The sustainability component — so far, the diesel fuel usage at the research station has been reduced by 80 per cent — was vital to its success.

Penn, whose team has been working with the region’s First Nations communities since the project’s inception, admits it “isn’t a silver bullet,” but it does have the potential to help address food insecurity in the Yukon.

“We’re not proposing these systems as a replacement for traditional growing, but it could help us understand better where hydroponic systems, indoor growing, could fit in as part of a broader food security system solution,” he says.

Fresh Routes & LeftOvers Foundation

Calgary, Edmonton & Winnipeg

The year 2020 is one Lourdes Juan, BGS’05, MEDes’10, will never forget. “I got married, got pregnant and now I’m Enzo’s mom!” she says with a hearty laugh. “Some pretty wonderful things happened.”

Of course, planning a wedding during a global pandemic — her guest list of more than 300 was whittled down to just immediate family — looked a lot different than it would have in normal times. Juan, though, found ways to pivot not only in her personal life, but also in her life’s work. It’s a vocation that feeds her soul and, in turn, feeds some of Calgary’s most vulnerable communities.

For nearly a decade now, Juan, who received her master’s degree in environmental design at UCalgary, has been finding innovative ways to both combat food waste and serve those in the community experiencing food insecurity. Since 2012, her LeftOvers Foundation has been redistributing unused food to underserved populations, to the tune of about 10,000 lbs of food per week in Calgary, Edmonton and Winnipeg, collectively.

Working with her regular partners, restaurants, bakeries and other food suppliers at the start of the pandemic last March, she and her team were able to quickly redistribute 27,000 lbs of food when those businesses were caught off guard and shut temporarily.

Juan’s newest project, Fresh Routes, uses a refurbished Calgary Transit bus that houses a mobile grocery store filled with fresh produce and other healthy food items, at prices between 25 and 40 per cent lower than those of regular grocers. “We saw that the LeftOvers model helped to bring food to agencies serving vulnerable Calgarians, but we also wanted to bring food directly to households,” she says of Fresh Routes, which also operates in Edmonton. The bus, along with several trucks, have removable carts that can be placed outside and will move into high gear this spring as the weather gets warmer and COVID-19 restrictions potentially ease.

Juan, who in 2020 was seen by the Al Jazeera TV network’s 40 million viewers in a feature on pandemic heroes, has high praise for organizations like the Calgary Food Bank. She sees her programs as another part of the “web” of services that reach out to those in need. Promoting sustainability — redistributing unused food rather than sending it to the landfill — and helping to stretch monthly grocery budgets make for a rewarding life, says Juan.

“It’s about bringing food dignity to people, offering them healthy food and doing it creatively,” she says.

“I’m an eternal optimist, but I know it can be done.”

Simon Farm Project

High River, Alberta

Over the past two decades, Dr. Tatenda Mambo’s educational pursuits have taken him from his home country of Zimbabwe to California and Ohio, before finally landing in Canada in 2009 to begin his PhD at UCalgary.

“I have no problem going to unfamiliar places,” says Mambo, PhD’16, of his peripatetic lifestyle. “I’ve always been good with people, so making new connections hasn’t been hard.” Still, toiling on a farm south of Calgary wasn’t where Mambo imagined his journeys would eventually lead him. “Being a farmer definitely wasn’t in the plan,” he says with a chuckle, noting that his childhood dream was to play professional basketball. “But I found I like getting my hands dirty.”

As co-manager of the 21-acre Simon Farm Project, Mambo, a post-doctoral scholar in UCalgary’s Sustainability Studies Program, oversees an enterprise that provides engagement and experiential learning opportunities in regenerative agriculture.

Along with getting his hands dirty, Mambo found he also liked — in fact, loved — the idea of applying his academic knowledge to producing food sustainably.

“What we want to focus on is nutritious food,” he says. “The key is to improve the soil at the same time we are harvesting crops from them.” The current practices of conventional agriculture rely on synthetic forms of nutrients to provide plant nutrition, such as chemical fertilizers and pesticides — practices that have been blamed for greenhouse gas emissions, soil degradation and water pollution. Regenerative agriculture, on the other hand, sees the integration of various forms of production, with those activities — which include biodiversity, nutrient cycling and environmental stewardship — functioning as part of a holistic ecological system.

Some of the many benefits of regenerative agriculture include reversing climate change by rebuilding soil-organic matter, which, in turn, will help to keep healthy the billions of acres of farm- and pasture land that feed the world today.

“We clearly can produce enough food to feed the world,” says Mambo, whose co-manager at the farm is Dr. Craig Gerlach, PhD, a professor in UCalgary’s School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape and the academic lead for its Sustainability Studies program. “But conventional methods, coupled with our current food system, have particular sustainability concerns with regard to the environmental and wider social impacts due to pollution, loss of ecosystem services, obesity and nutrient deficiencies, food waste, and loss of genetic diversity.”

The Simon Farm Project, a five-year partnership with the land’s owner, John Simon, and UCalgary’s Sustainable Energy Development (SEDV) program, has grown a wide variety of vegetables, along with hops for Alberta breweries — a testament to its overseers’ commitment to biodiversity and growing with the intent to regenerate, rather than degrade, the soil.

“This can be an illustration of how we can shift agricultural practices in our region,” says Mambo, who is more than happy with his unexpected turn as a farmer. “We want to open people’s minds to better ways of doing things.”