Written by Marcello Di Cintio, BSc’97, BA’97

Photographed by Bryce Meyer

It’s late morning at the Dashmesh Culture Centre (DCC) in the northeast community of Martindale. In the basement langar hall, diners line up to fill their steel thali trays with dal, channa masala, sweet rice and fresh salad. Metal tumblers of drinking water crowd one table. Thin rubber mats lay in straight lines on the linoleum floor where diners sit cross-legged in front of their meals. A volunteer with an urn and a basket walks up and down each row offering cups of chai or rounds of fresh roti for anyone who needs an extra circle of bread.

When they’ve finished eating, each diner, with turmeric-dyed fingers, will rise to bring their trays to the dishwasher and along the row of sinks at back of the hall. All the while, music from the upstairs gurdwara, performed live throughout the day by a rotating trio of white-turbaned musicians, emanates from ceiling speakers.

The Sikh concept of langar originated more than a half millennia ago when Guru Nanak Ji was on his way to the market. Nanak Ji would eventually found the Sikh faith, but, when he was 12 years old, his father worried about his future. As befits a future guru of his stature, Nanak Ji preferred the company of holy men to businessmen. This troubled Nanak Ji’s father, a wealthy trader, who wanted his boy to develop his own entrepreneurial skills. So Nanak Ji’s father gave his son 20 rupees and sent him off to purchase salt, turmeric and other goods to trade for a profit.

En route, Nanak Ji came upon a group of hungry sadhus meditating in a forest. Each had sacrificed worldly comforts for spiritual gain. Nanak Ji said to his travel companion, “What better bargain could there possibly be! Let us offer the money to these fine holy men. They will eat and buy clothes and they will be pleased!” The sadhu leader refused the money, but Nanak Ji purchased food for them from a nearby village. Nanak’s father was furious that his son came back empty-handed, but Nanak Ji explained that true profit was found in feeding the needy.

Guru Nanak Ji’s act of compassion has lived on. Nearly every gurdwara in the world runs a community kitchen that serves free meals to all comers. Some are modest facilities that might provide a meal every week, while the largest gurdwaras in India serve hundreds of thousands of meals each year. The cuisine is always democratically vegetarian. Everyone can partake, regardless of their dietary regulations.

And everyone sits on the floor, “so, whether you’re a king or whether you’re poor, no matter who you are, you sit at the same level and you eat,” says Jagjeet Kaur, a third-year education student at the University of Calgary who prays daily at the DCC. Kaur’s family has long supported the langar through financial donations; they might cover the cost of a week’s worth of langar, for example. Kaur, herself, is a member of the near-300-person strong battalion of volunteers who can be summoned at any time to help out in the langar hall’s vast industrial kitchen. The langar has a large pool to draw from: more than 100,000 Sikhs currently reside in the city — a fifth of all the Sikhs in Canada — and the community is growing.

So, too, is the Sikh Studies program in the Faculty of Arts. A successful crowdfunding campaign in April 2021 raised $510,000 in just three weeks, more than twice the fundraising goal. This will result in a more robust program with additional courses, more research and community engagement, and the possible creation of a Chair of Sikh Studies.

The DCC translates the tradition of langar into the context of life in contemporary Calgary. The DCC provides it every day of the week, starting in the morning until around nine at night. Anyone who is hungry is welcome, from gurdwara worshippers and international students to single moms.

“Maybe some of them are suffering from addiction, or mental health issues or just down on their luck,” says Raj Sidhu, DCC’s director of operations. “Just, honestly, really good people.” Nobody asks guests why they are there. Nobody asks them to reveal their income or expenses or other such poverty credentials. And they endure no such interrogation and no proselytizing. Nobody gets a sermon. Everybody gets fed.

And Sikh tradition dictates strangers always get fed first. According to Dr. Harjeet Grewal, PhD, adjunct professor in religious studies at UCalgary, the writings of Bhai Gurdas state that Sikhs prepare food for everyone irrespective of need, then serve those people. “They eat after everyone,” Grewal says. “If there’s nothing left, which is unlikely, they go hungry.”

Regardless of the imperative to feed the needy, the langar tradition adheres more to the Sikh notion of equality and equitable access to necessities more than it does Judeo-Christian notion of giving alms to the poor.

“Regardless of your gender, your religion, your ethnicity, your culture, whatever it might be, inside you is the light of God,” Kaur says. Thus, everyone deserves to eat. In some respects, langar hardly resembles charity at all, which too often demeans a recipient’s sense of self-worth. The Sikh exchange of food exists outside the typical “have” and “have not” dynamic. Langar is wholly democratic. Meals are not given and received. They are shared.

In Calgary, the langar acts as the de facto interface between the city’s Sikhs and the greater community. Not only does the DCC serve hot meals to Sikhs and non-Sikhs, the DCC kitchen supports more than 30 food-security agencies throughout the city. The Calgary Food Bank receives meals from the DCC, as does the Leftovers Foundation, Salvation Army and Brown Bagging for Calgary’s Kids.

The DCC also runs its own food bank and hamper program called No Hungry Tummy. A trailer parked outside the gurdwara holds wire-rack shelves laden with decidedly non-Indian foodstuffs like pasta, peanut butter and Nutella. Unlike other local food agencies that require clients to prove their need, an exercise that can be demoralizing, the DCC’s hampers go to anyone who requests one, without question. In 2021, the program distributed 3,500 food hampers to needy families.

The Sikh exchange of food exists outside the typical “have” and “have not” dynamic. Langar is wholly democratic. Meals are not given and received. They are shared.

Volunteering at the langar hall has always felt meaningful to Kaur — “You want to be there to serve people because God is always there for you,” she says — but felt even more vital as waves of the COVID-19 pandemic crashed over Calgarians. COVID closed businesses and robbed workers of their jobs and livelihoods. As the community struggled, the need for langar increased.

The gurdwara saw an especially large uptick in hamper requests once the federal Canada Emergency Response Benefit program ended. People required help more than ever before. Many turned to the DCC.

Kaur volunteered at the gurdwara nearly every day during the pandemic. She prepared food and packed meals for delivery to needy households. Many people who would’ve normally come to the langar hall for a meal were in quarantine or isolating at home, so Kaur and her fellow volunteers took the food to them.

Not only the housebound received food assistance from the DCC. In February 2021, the centre’s volunteers prepared and delivered meals to demonstrators marching in solidarity with the Indian farmers’ protests, then again to truckers stranded by the British Columbia floods the following November. For the better part of a week, caravans of volunteers shuttled food all the way from Martindale to Golden, B.C. When convoy protestors blockaded the border at Coutts in February 2022, volunteers crossed into the U.S. at another port of entry to bring meals to truckers trapped on the American side. DCC’s crews delivered food to the Coutts protestors, too. “There was no differentiating. If anybody requests a meal, we will serve the meal,” Sidhu says. “We just counted how many truckers were stuck.”

Providing meals to people on both sides of a conflict adheres to the core philosophy behind langar: politics doesn’t matter. Nor does anger or hurt feelings. Everyone deserves to be fed, friend or foe.

“It’s about trying to see God in all, whether they seem to be your enemy or not,” Kaur says. “At the end of the day, even though they’re looking down on you, you still see the good in them. And you still offer them that meal.”

In June 2021, the DCC expanded its service to the community with what could best be described as a langar of vaccines. A Sikh doctor who works with the Siksika First Nation reached out about running a vaccination clinic out of the DCC. Through a collaboration with the Calgary Homeless Foundation and Okaki — a medical software provider specializing in Indigenous health — more than 700 people received COVID vaccinations in the langar hall. “It’s been amazing to see the Indigenous community and the Sikh community here in Calgary develop that strong bond and work together,” Sidhu says.

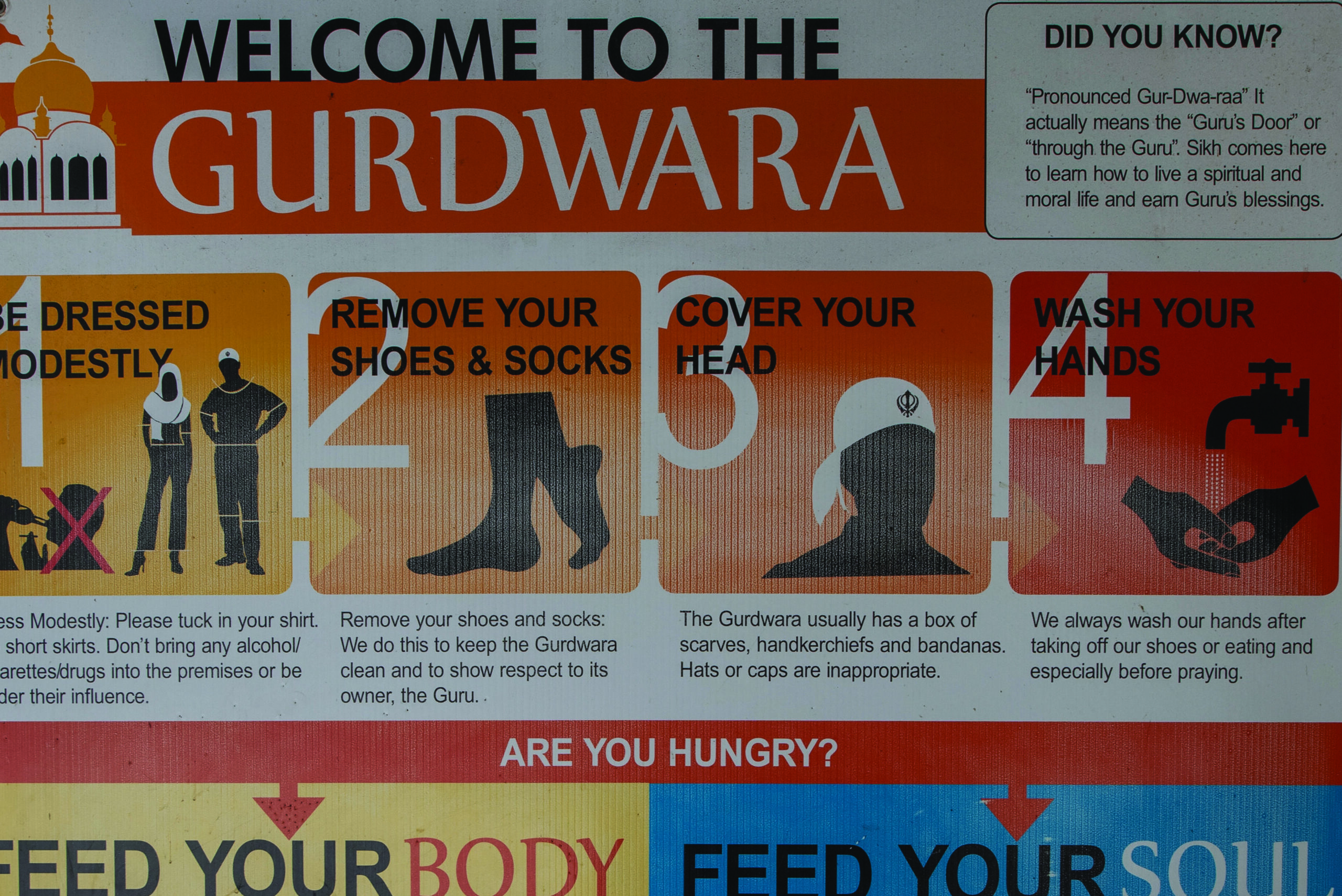

The program was profoundly successful. Due in part to the DCC’s vaccination efforts, Calgary’s upper northeast boasted Canada’s highest immunization rate. By November 2021, the Calgary Herald reported, more than 99 per cent of the area’s residents 12 and older had received their first dose of vaccine. And not just Sikhs. “A lot of people that are non-Sikh came here, and we’re proud of that,” Sidhu says. Everyone respected the gurdwara’s rules. They covered their heads and removed their shoes. “There were no issues. Everyone was friendly and appreciative of the program.” Perhaps counterintuitively, the pandemic strengthened the bonds between Calgary’s Sikhs and the community at large.

The imminent expansion of the Sikh Studies program feels important for young Sikhs like Kaur, who contributed to the crowdfunding campaign. Kaur realizes few non-Sikh Canadians know anything about Sikhism, even though the country’s half-million Sikhs represent the highest population of Sikhs outside of India. “A lot of times, we’ll be mistaken as Muslims, or we’ll be mistaken as Hindus,” Kaur says. “But the Sikh faith is a completely separate sovereign faith. So it’s really cool that people are getting that knowledge.”

Spreading this knowledge is vital. “Sikhs believe in the ethos of this country,” Grewal says. “But the country needs to know what our ethos is, and how they connect.” Non-Sikhs don’t realize how closely their values align with Sikh values. An enhanced program will serve to fill in those gaps. Grewal sees a kinship between the philosophy of langar and the expansion of the Sikh Studies program. Both are rooted in the concept of engagement.

“Expanding into course offerings is the same impulse,” Grewal says. “This is what I get from my students: ‘We want to share what we do.’”