Written by Jaelyn Molyneux, BA’05

John Patten was two and a half when he was enslaved to Mrs. Pritchard. Pero was purchased for a horse and eight guineas. Phillis was left to the wife of Samuel Hallett in his will. When Ben ran away, he took three sailor jackets with him. Eve was one of the best servants for washing that John Rapalje ever had.

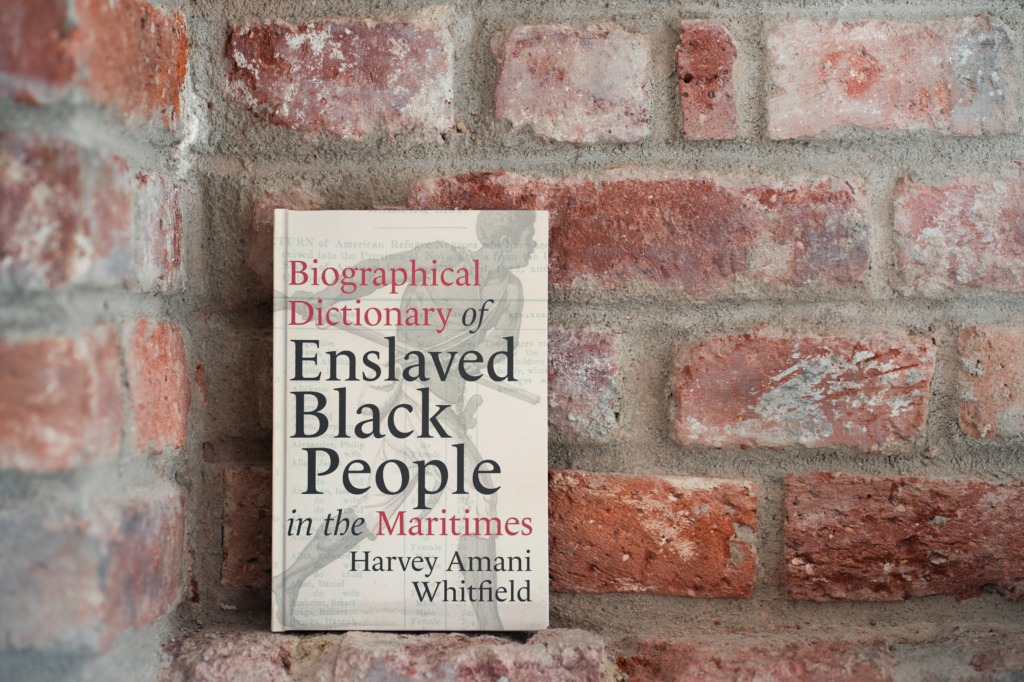

Those are just some of the details we know about 1,465 enslaved people in Canada. Their stories were collected by Dr. Harvey Amani Whitfield, PhD, for his book, Biographical Dictionary of Enslaved Black People in the Maritimes from the University of Toronto Press.

The book is the University of Calgary history professor’s sixth. His previous books including Black Slavery in the Maritimes: A History in Documents and North to Bondage: Loyalist Slavery in the Maritimes required him taking deep dives into the documentation of slavery. Those documents were the inspiration for the biographical list in this book.

“In the beginning, I wrote down slave-owners’ names,” says Whitfield. “It literally started as a list. Then I might add the slave names. I kept doing this over and over.” He worked on this for years, sifting through notices about runaway slaves, bills of sale, probate records, baptism records, court documents — whatever he could find from the seventeenth through early nineteenth centuries.

The documentation available is thin.

“The archive silences enslaved people,” says Whitfield. “Because they were enslaved, we don’t get that documentary evidence.” And what is available often takes some decoding. Black people listed as servants could have been enslaved. Some came to Canada free and were re-enslaved. Others came as slaves and were freed. They could be traded back to the West Indies or come to Canada from the U.S. as Black Loyalists.

The story of slavery in the Maritimes is brutal and complex, set up against the backdrop of a pre-Confederation Canada trying to figure itself out in the wake of the American Revolution, a changing British Empire, surging population and fumbling local governments.

And every slave had their own story. “Enslaved people are not all the same,” says Whitfield. “They didn’t all have the same experiences.”

His biographical list gets into those details, including the skills, family structures, and journey of the men, women and children. It is far from complete — Whitfield and his graduate students continue to dig up more names and details — but it is a record of hundreds of lives of enslaved people. “This book bears witness to their existence,” Whitfield says in the introduction.

Here are some of the 1,465 records, as excerpted from Biographical Dictionary of Enslaved Black People in the Maritimes.

Diana Bastian (c. 1792, age 15)

An Anglican Church recorder memorialized the sad life of young teenager Diana Bastian (her surname has been spelled various ways: Bustian, Bastian, and Bestian) in this burial record. His extraordinary account highlights the brutal life of Bastian, but also her refusal to allow George More (who was much older than Bastian) and his powerful friends to dehumanize her. The church’s documentation illuminates the way one young enslaved girl fought against her tormentor: “Buried Diana Bastian a Negro Girl belonging to Abraham Cuyler [former mayor of Albany, New York], Esq. in the 15th year of her Age, she was Deluded and Ruined at Government House by George More Esq. the Naval officer and one of Governor Macarmick’s Counsel by whom she was pregnant with Twins and delivered [of], but one of them; She most earnestly implored the favour of Mr. More’s Brother Justice’s to be admitted to her oath, concerning her pregnancy by him, but was refused that with every other assistance by him & them.”

Source: September 15, 1792, Burial Record 1785–1827, St. George’s Anglican Church, Sydney.

Flora (c. 1780s)

Flora was enslaved to Hannah Lee in Marblehead, Massachusetts, and was probably enslaved to the Robie family in Halifax. When Hannah Lee died, she did not free Flora, but gave her several items. Flora went to Halifax to live with Mrs. Lee’s granddaughter, Mary Bradstreet Robie, who owned Flora’s daughter. Clearly, the Robies knew that Flora would come and serve them because she wanted to be with her child.

Source: G. Patrick O’Brien, “‘Unknown and Unlamented’: Loyalist Women in Nova Scotia from Exile to Repatriation, 1775–1800” (PhD dissertation, University of South Carolina, 2019), 203–6; O’Brien to Whitfield and Chute, private correspondence, December 17, 2020.

François (c. 1742)

Ken Donovan’s work to discover the fascinating story of François is a masterpiece of historical research. Using the records of Martinique’s Superior Council and correspondence with Louisbourg officials, Donovan illuminates how François ended up in Louisbourg and eventually married and had a modicum of independence that most other slaves did not enjoy. In 1740, the commissaire-ordonnateur requested a slave to serve as executioner. Martinique’s Superior Council decided to send François, who had been convicted of murdering a small Black child (he was given a choice of going to Île Royale or being executed). The Intendant of Martinique purchased François and allowed him to practise the skills necessary to be an executioner. Once in Louisbourg, the government provided François with 300 livres per year, rations, and purchased a wife for him. As Donovan states, “Clearly, François and his bride, although still slaves, were granted a measure of independence.”

Source: Donovan, “Slaves and Their Owners in Île Royale,” 19.

Robert Gemmel (c. 1791)

Robert Gemmel almost suffered re-enslavement and sale out of Nova Scotia, but it was prevented by his mother named Susannah Connor, who “came here personally into Court” and complained that one John Harris intended to take her son out of the province. Her son [Robert Gemmel or Gammel] worked as Harris’s indentured apprentice. The court ordered Harris to come in immediately and answer for his alleged plans. Harris readily admitted that he planned to leave the province, but claimed that the only reason he planned to take the boy was because there were no other available owners to teach Gemmel the art of butchery. The court cancelled the indenture. If Susannah Connor had not intervened on behalf of her son, Gemmel would have been taken out of the province – to the United States or elsewhere – and no doubt enslaved. The case of Robert Gemmel underlines the tenuous nature of the line between slavery and freedom that Black people faced in the Maritimes, even – perhaps especially – if they were small children.

Source: General Sessions at Shelburne, Nova Scotia, November 1, 1791, Shelburne Records, MG 4, vol. 141, NSA.

Lymas (c. 1784)

John Wentworth sent Lymas and 18 other slaves from Nova Scotia to his “relation” Paul Wentworth in Suriname. Wentworth described these slaves as, “American born or well seasoned, and are perfectly stout, healthy, sober, orderly, Industrious, & obedient.” Wentworth had the slaves Christened and claimed to be concerned for their welfare. He noted that “Lymas is a rough carpenter & Sawyer.”

Source: John Wentworth to Paul Wentworth or his attorney, February 24, 1784.

Unnamed Man (c. 1751)

In 1751, 10 slaves were offered for sale in Boston after arriving from Halifax. The advertisement read: “JUST arriv’d from Hallifax, and to be sold, Ten hearty Strong Negro Men, mostly Tradesmen, such as Caulkers, Carpenters, Sailmakers, Ropemakers: Any Person inclining to purchase may enquire of Benjamin Hallowell of Boston.”

Sources: Boston Post Boy, August 8, 1750; Boston Post Boy, September 23, 1751.