Written by Jaelyn Molyneux, BA’05

Artificial intelligence (AI) is already all around us. You’ve experienced it today if you opened your phone using face recognition or watched something suggested to you by Netflix.

ChatGPT is the AI celebrity of the moment, but there is so much more to the present and future of AI.

It’s helping with huge advancements in health-care diagnostics and patient care. It reduces human error and allows for more precise decision-making. It’s solving complex issues that our human brains can’t compute on their own.

So, what triggered the sudden explosion of AI? Data, baby.

We’ve been gathering digital data for several decades now and industries across the board are getting better at collecting it and making it available to ever-improving computing systems.

AI uses machines to do things that usually involve human intelligence. The technology is trained to understand the environment around it or understand language. It can identify patterns and make predictions. It can make recommendations. It learns how to do all of that because it has access to lots of information.

“The advent of big data sets has been the starting point for the current AI revolution,” says Dr. Joon Lee, PhD, who leads the Data Intelligence for Health (DIH) Lab based out of the University of Calgary’s Cumming School of Medicine (CSM). DIH researchers bridge the gap between data science and health research by applying machine learning or AI to really complex data.

The lab collaborates with other researchers across health disciplines and starts with identifying a problem they want to tackle and a data set that can help solve the problem. Before AI gets involved, researchers make sure they understand the data, clean it up and fill in gaps. With clean and prepared data, they can apply algorithms to give the machine its intelligence. A critical part of the work in Lee’s lab is checking the performance of the AI to make sure it is accurate and delivers useful information to the user.

“Despite the focus on AI, every step of the way there is something that humans have to decide on,” says Lee.

His is just one UCalgary lab that uses AI as a tool. Here are a few other ways researchers at the DIH Lab and across the university have used AI to try and make the world a better place.

Monitoring junk food marketed to kids

Advertising is, by nature, targeted and manipulative. A machine learning system created by the DIH Lab in collaboration with Dr. Dana Lee Olstad, PhD, an associate professor at CSM and the Faculty of Kinesiology, monitors food ads that target kids on websites and social media. It can tell if an ad is about food based on the visual features of the ad. And, by looking for indicators identified by Health Canada like specific colours, cartoon characters, or cross-promotional links to games or prizes, it can tell if marketing is aimed at kids versus adults. Those ads are then connected to nutritional data to calculate if the food being marketed is healthy or not. That information is shared in real time on interactive dashboards. The goal is to help policymakers improve child health by giving them data on how much kids are exposed to marketing of potentially unhealthy food.

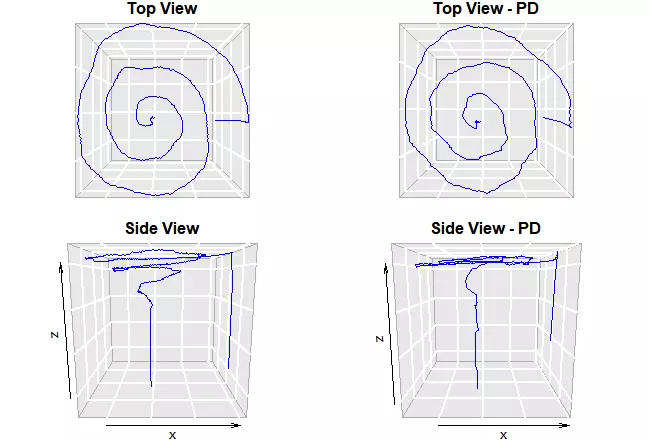

Detecting Parkinson’s from digitized handwriting samples

A spiral drawn on a tablet can detect Parkinson’s disease and other movement disorders. It can also track how well treatments are working. When someone draws that spiral, they are sharing all sorts of data, including pressure and recurring patterns. Those digital biomarkers are collected using a tool designed by the CSM and researchers from the Calgary Parkinson’s Research Initiative that sees that data as a shape. Data can be analyzed on a simple device like a tablet and doesn’t need large datasets. This makes testing quicker, more accessible and less invasive.

Creating a better road map for trucking goods

AI is being used to study tens of millions of GPS records identifying traffic patterns and driver behaviour in all sorts of weather. It’s all in an effort to help the trucking industry get loads of goods from one place to the next in the quickest, safest way possible. That also helps to reduce emissions. Dr. Xin Wang, PhD, a geomatics professor at the Schulich School of Engineering (SSE), is working with the National Research Council of Canada, The City of Calgary and transportation companies to use machine learning to optimize route and workforce planning and delivery schedules.

Identifying fraudulent websites

Have you ever been worried about fraud when you buy shoes, or anything else for that matter, on the internet? The internet is riddled with fraudulent websites tricking consumers into handing over their credit card or other financial information. The nefarious fraudsters are hard to detect because of the complicated layers of third-party providers — many legit — sharing information behind the scenes to complete the transaction. The bad actors also quickly vanish before they are traced. Researchers at UCalgary’s Haskayne School of Business and the University of Warwick in the U.K. developed algorithms that use machine learning to detect fraudulent websites. This work builds on earlier work they did building algorithms to suss out fake news.

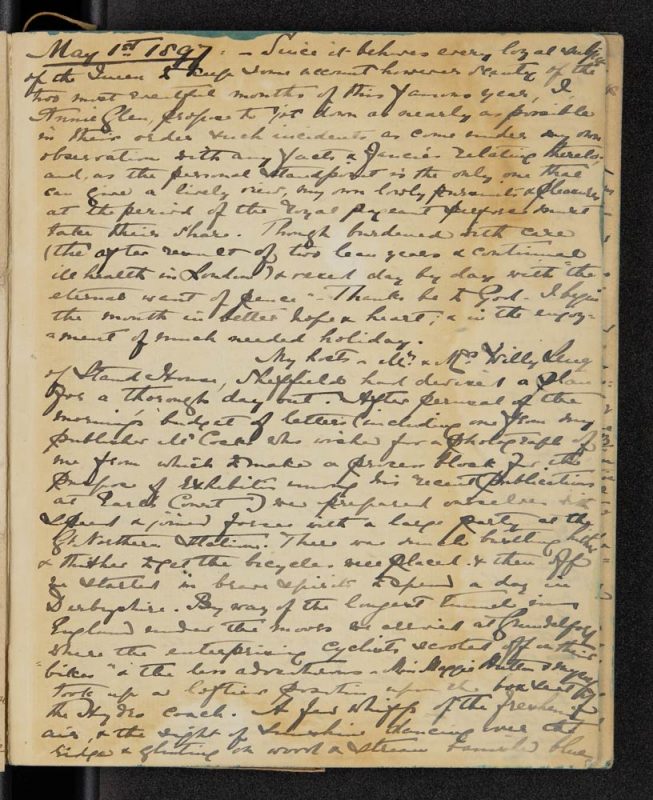

Understanding and preserving old handwriting

It can be challenging to understand your own handwriting; now, imagine how hard it is to understand writing from decades or even centuries ago when the script may have been extra-swirly, different words may have been used and there was just so much of it. UCalgary’s Libraries & Cultural Resources is using AI, specifically handwriting text recognition, to transcribe registers and diaries from as far back as the 1890s. It’s using Transkribus, a platform developed at the University of Innsbruck in Austria that looks specifically at historical documents. Transkribus creates a model by studying a batch of digital images with writing by a single author to learn their nuances (Is that a “c” or an “e”?) before large bodies of that author’s work is transcribed. Digitizing that work preserves it and makes it more searchable and accessible to modern and future researchers.

Smarter detection of natural gas leaks

Invisible to the naked eye and a basic camera, it takes an infrared camera to see natural gas leaks. And, while that camera might be able to see the leak, another tool is needed to measure the emission rate before anything can be done about it. That process is time-consuming and clunky. Dr. Ke Du, PhD, an associate professor with the Department of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering at SSE, wants to use AI to make those infrared cameras smarter so they can not only find a leak, but also quantify it and trigger an alarm in real time so leaks can be stopped quickly. Monitoring would be automatic, continuous and accurate.

Using wearables to help with aging at home

This is not about location tracking or getting an alert when your aging mother falls. It’s about collecting personalized data for precision health care so Mom can make decisions about aging in place safely, for as long as she wants. The DIH Lab used wearable devices to collect information about an individual such as their heart rate, sleep patterns, movement and more. Based on patient-generated data collected over time, researchers created algorithms to track and predict the progress of frailty and fall risk.

Using decades of data to improve coronary artery disease patient care

AI starts with data and the Alberta Provincial Outcome Assessment in Coronary Heart Disease (APPROACH) has a lot of it. The cardiac registry started in 1995 and includes information collected over decades from hundreds of thousands of patients with coronary artery disease about characteristics, treatments and outcomes. It can isolate groups based on sex or age or people with co-morbidities like diabetes. APPROACH is one of the largest and most comprehensive cardiac registries in the world. The DIH Lab uses AI and develops algorithms to dig into the APPROACH data to help clinicians, patients and their family make better treatment decisions.