Photography by Dustin Patar

Written by Jacquie Moore, BA ‘97

If you look at the image on the back of the current Canadian $50 bill, you’ll have an idea of where Dr. Brent Else, PhD, has spent nearly a years-worth of his days over the last couple of decades.

Else, BSc’05, MSc’08, is an associate professor and researcher in the Faculty of Arts’ Department of Geography at the University of Calgary, as well as acting executive director of the UCalgary-based Arctic Institute of North America. He recently served as chief scientist on the Amundsen — Canada’s only icebreaker dedicated to Arctic research — scheduling, co-ordinating and liaising between the 35 researchers on board and the 40-person strong Canadian Coast Guard crew.

It was an around-the-clock gig on which Else was more than pleased to embark: the seawater and other samples collected by scientists from across the country, including by Else himself, will help answer urgent questions about why the Arctic is warming four times faster than the rest of the planet.

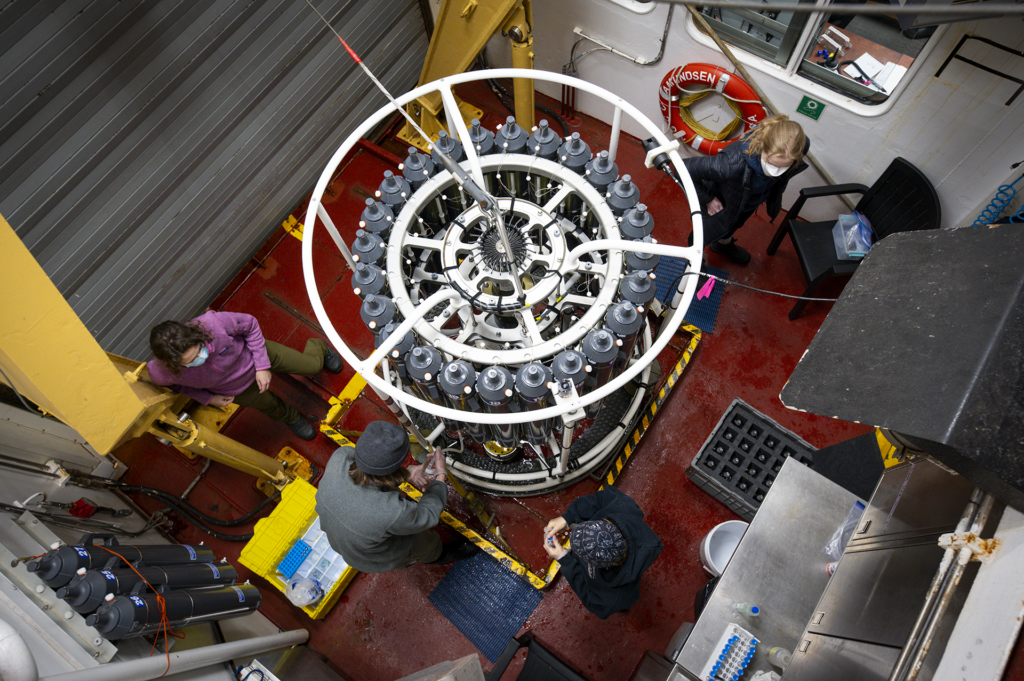

Retrofitted from circa-1979 icebreaker to state-of-the-art oceanography research vessel, the Amundsen (previously known as Franklin and later the Sir John Franklin) supports national and international multidisciplinary research programs. The vessel’s pool of equipment is managed by the non-profit Amundsen Science (which also deploys the ship’s annual research expeditions) and includes 65 scientific systems and 22 on-board and portable laboratories built to accommodate the needs of physical, chemical, and biological oceanographers, paleoceanographers, geologists, atmospheric scientists, remote-sensing specialists and epidemiologists.

Simply put, if you’re a researcher with an interest in the Canadian Arctic, the Amundsen is your space station.

As the vessel pushed through icy waters around Baffin Island and northern Quebec for three weeks in October 2023, Else aimed to ensure that the three dozen scientists it carried from universities across the country were able to focus solely on their research. When asked how he’d describe what he did in a day as chief scientist on the vessel, Else answers with a comical understatement: “I wandered around.” In fact, his role was key to the smooth operation and success of the expedition.

Captivated by his undergraduate experience as a research assistant on a polar-sea expedition, Else’s interest in Arctic marine environments led him to his own current research examining the cycling of greenhouse gases in the ocean. By analyzing the ocean “carbon sink” — a.k.a., ocean acidification — he is working to advance understanding and predictions of our changing climate. Discovering an answer to a very big question —how much human-produced carbon dioxide is being absorbed by Canadian Arctic waters? — will be enormously important to current and future marine and human life.

Life on board an Amundsen expedition is both exacting and unpredictable, as the vessel is at the mercy of shattering sea ice and Arctic storms. Every evening, Else would meet with the scientists to gather requests about what they were seeking in terms of sample collections over the subsequent 24 hours as the ship made stops at numerous hydrographic stations in Foxe Basin and the Hudson Strait — a route designed by Else in collaboration with the Coast Guard and Amundsen Science. (In terms of Else’s research, the Foxe Basin, located between Baffin Island and Nunavut’s Melville Peninsula, is, he says, “a missing piece of our puzzle in our understanding of how much CO2 the Arctic absorbs.”) Else would then liaise with the captain and chief officers to ensure the right instrumentation, equipment and labour would be available to collect seawater, plankton or other specimens as requested. “That’s how we would predict who would need to be up at, say, 3 a.m. to gather their requested sample,” he says.

Working alongside the crew, Else was able to gather seawater samples in bottles lowered into the ocean at various depths. For scientists studying marine life, the crew would use nets to catch fish and zooplankton, including for a study on the abundance of species at various depths. A researcher exploring past climates and environments was able to analyze ocean sediment that was collected with a coring instrument.

Throughout his days, which started at 7 a.m., Else would visit each researcher and field more requests as they came in. “I’d be back and forth all day between the labs and the captain and chief officers, conveying requests from the scientists who wanted to collect various samples that required the use of all kinds of equipment — cranes and winches, etc., operated by the coast guard crew,” he says.

Else says that, for him, it was a daily exercise in finding the balance between scientists’ needs and the Coast Guard’s capacity and duties. “My colleagues and I would discuss what we’d like to achieve, but the captain and crew would have the final say on what was possible,” he says.

Along the way, Else and his colleagues found fun when they could. During breaks from lab work, movie nights and games of foosball, darts and cards enlivened Amundsen’s lounge (a “dry” i.e., alcohol-free environment onboard since last year). Meals were communal and vibrant discussion and debate was ongoing.

“A large part of being on an expedition like this is the opportunity to build collaborations with fellow scientists and with the Coast Guard crew,” says Else, who hopes to return to Foxe Basin in 2024 to continue his research.

Named for the early 20th-century polar explorer, an Amundsen expedition is perhaps a microcosm of what it will take to address some of the most urgent climate challenges of this century: adaptability, camaraderie and courage to make waves in pursuit of transformative change.