Another secret we carry is that though drab outside — wreckage to the eye, mirrors a mortification — inside we flame with a wild life that is almost incommunicable.

from The Measure of My Days by Florida Scott-Maxwell, written from her nursing home at the age of 82

Written by Jacquie Moore, BA’97

There’s a New Yorker cartoon featuring an unhappy-looking older man with a long beard sitting at the window of his Manhattan apartment with a shotgun on his lap. His wife, unalarmed and lounging in an armchair nearby, is saying into the phone, “He’s angry because he’s getting old.”

And why shouldn’t he be? Getting old in this part of the world often means being relegated to the category of unseemly “other,” a group that — says Dr. David Hogan, MD, a professor and geriatrician at the Cumming School of Medicine (CSM)— is largely seen as some combination of incompetent, burdensome, non-sexual, unambitious, senile, sad, confused and, overall, acceptable fodder for greeting-card jokes.

While many cultures, including Indigenous peoples and Asian communities, have traditions of respect for older persons, Western attitudes toward aging are often negative. A growing body of research shows the dire consequences of ageism to health and to health-care costs.

“To perceive older persons as helpless is a dangerous and patronizing perspective,” says Hogan. “It feeds into this youth-centred idea of power and privilege — the idea that older individuals are not full members of society. It’s a dismissal of the abilities and strengths they bring to the conversation.”

Like other destructive “-isms” in our culture, ageism against older people is based on a rejection of perceived differences in a certain group. Notably, however, for the first time, the older-adult set is getting ahead: in Canada, there are now more people aged 65 and over than those 14 and under.

Hogan and his colleagues at the Brenda Strafford Centre on Aging in UCalgary’s O’Brien Institute for Public Health work to illuminate ageism in its many forms. Hogan says the COVID-19 pandemic often shone a bright light on hostile or “calculated” ageism; he recalls comments made by Texas Lt. Governor Dan Patrick in the early part of the pandemic that suggested older people consider sacrificing their lives so the younger generations could get the economy going again. (The same senator blamed unvaccinated Black people for the spread of COVID in his state.) More prevalent than hostile ageism, however, is our culture’s widespread, habitual brand of “benevolent” or “compassionate” ageism.

“People are often motivated by the best intentions and don’t realize what they’re doing,” says Hogan. “Benevolent ageism sees old people as one homogenous group that needs protection and help in deciding what is best for them.” For example, he says, an intervention for an older person at risk of falling might be, “they shouldn’t walk on their own, they need to stay in a wheelchair,” says Hogan. While, in some cases, after considering the options and their potential consequences with the older person, there is a shared consensus that this may be the best solution, sometimes “such a decision can have such a nefarious impact on the individual’s life that is ultimately worse than a fall, if it’s not what the person wants.”

Limiting older individuals’ autonomy around decision-making and excluding them from participating in activities is associated with worse health outcomes, says Dr. Jayna Holroyd-Leduc, MD, an academic geriatrician and professor at CSM. She points to a recent systematic review that shows how ageism negatively impacts everything from the older person’s access to work opportunities and health services to a decline in mental health and poor social relationships.

“At the structural level, we see ageism in the way that policies and practices support health care-rationing by age,” says Holroyd-Leduc, who will take over as academic lead of the Centre on Aging this summer, recently gave a public lecture on ageism organized by the Calgary Chapter of the Alberta Association of Gerontology. At an individual level, she says, “we see ageism in the ways an older person takes in negative cultural views of aging, including self-limiting behaviours.” Or, as Hogan puts it: “learned helplessness.”

Another common example of benevolent ageism is “elderspeak,” defined by Hogan as, “a form of communication overaccommodation used with older adults that sounds a lot like babytalk.” The negative impact of speaking more slowly with simpler words and sentences to an older person on the assumption that their thinking abilities have declined often makes communication worse, not better, he says. “People don’t realize the harm they’re doing by lumping all older individuals in the same bucket and viewing them as mentally incompetent and vulnerable.” Hogan adds that pandemic-era media, which combined the words “vulnerable” and “seniors” constantly in the news, hasn’t helped matters.

So, what can be done to shift behaviours that put one of the country’s fastest-growing demographics on the shelf? Holroyd-Leduc and other researchers at the Centre on Aging strive to improve the mental and physical health of older adults through increased social participation, age-friendly communities and policies that promote equitable inclusion in society.

Holroyd-Leduc says that, “addressing ageism needs to become a health-care priority.” Current and new health policies should, she says, “be reviewed to ensure they don’t promote inequities by age, and funding agencies should establish requirements for inclusion of older adults in medical research.”

Speaking more slowly with simpler words and sentences to an older person on the assumption that their thinking abilities have declined often makes communication worse, not better.

As well, Holroyd-Leduc would like to see the incorporation of ageism-awareness into education curriculums. “We need to create opportunities for young people to learn from older adults, which could include situating schools, daycares and university dorms within continuing-care facilities,” she says, adding there should also be more intentionally designed outdoor spaces and parks that include multigenerational outdoor exercise equipment and accessible community gardens. A new emphasis on positive presentations of older adults on social media and in TV and film would also help with a cultural shift (see pg. 39 for details about a local older person-affirmative film festival).

Perhaps, Hogan says, one of the most helpful things we can do is to remind ourselves, “that we all live at some risk.” All of us, whatever our age, he says, “should be able to judge what types of risk we are willing to live with, as long as we fully understand our situation and what our options are, based on our values and beliefs.”

Certainly, it can be difficult to determine when help is truly helpful and when it’s potentially harmful, but, says Hogan, “when we do intervene to help someone, it should be based on facts and one’s needs at that time, not on an assumption that they lack ability or don’t have the wherewithal to live their life as they wish.”

Support and care, he adds, should be approached whenever possible as making decisions with rather than for others. “We want to support autonomy, not helplessness.”

The Silver Screen

Calgary’s THIRDACTion Film Festival puts the beauty, complexity and appeal of ageing front and centre.

Written by Lois Epp

The brainchild of Mitzi Murray, Calgary’s THIRDACTion Film Festival launched in 2017. With more than a quarter of Canada’s overall population living into their 70s, 80s and 90s, Murray saw the opportunity to showcase what positive aging and a productive “third act” can look like.

As Murray explains, “media is often fraught with negative stereotyping, and the medicalization of aging leads audiences to believe that aging is nothing but decline and frailty. Symbolic annihilation is another significant contributor. To put it simply, when we don’t see ourselves represented in the media we consume, we start to believe that we don’t matter.”

But someone needs to be the disruptor and flip the script. Cue Murray, whose observation of the adverse effects of sidelining seniors during her work in seniors’ housing inspired her passion project, which is equal parts advocacy, entertainment and education.

UCalgary’s Brenda Strafford Centre on Aging, which lives and breathes the health and wellness of older Canadians, is a founding sponsor of the festival, including the Reel Research Speaker Series, where subject-matter experts from UCalgary and beyond participate in post-screening discussions related to aging topics that appear in the films.

Now in its fifth year, THIRDACTion has hit its stride. Ironically, thanks in part to the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting opportunity to expand the festival offering monthly online screenings to a larger, housebound audience. To learn more about the festival, visit thirdactionfilmfest.ca. And, here are some favourite films that have screened at the festival:

Gun Killers

Canada, documentary; short

In an undisclosed location in rural Nova Scotia, retired blacksmiths John and Nancy Little live a peaceful life, tending to their beautiful vegetable garden and crafting ethereal musical sculptures out of scrap metal. Occasionally, the couple are employed by local police to engage in the mass destruction of firearms in a noble effort to protect the lives of all Canadians.

Ladies of Steel

Finland, comedy

After hitting her husband on the head with a frying pan, Inkeri, 75, flees with her two sisters, Raili and Sylvi. Their journey through Finland is filled with charming hitchhikers, memories and sinful dancing. When Inkeri comes across her old university writings and finds Eino, a crush from her youth, she’s reminded of her dreams that were later suppressed by a patriarchal marriage. Inkeri must make the biggest choice concerning the rest of her life, a choice between happiness and convention.

When Tomatoes Met Wagner

Greece, documentary

In a dying Greek village, two cousins and five women decide to do things differently. With a little help from Richard Wagner’s music, the villagers cultivate an ancient tomato seed and enter the world market with their organic products. Humorous and bittersweet, this surreal story speaks about the importance of reinventing oneself during difficult times.

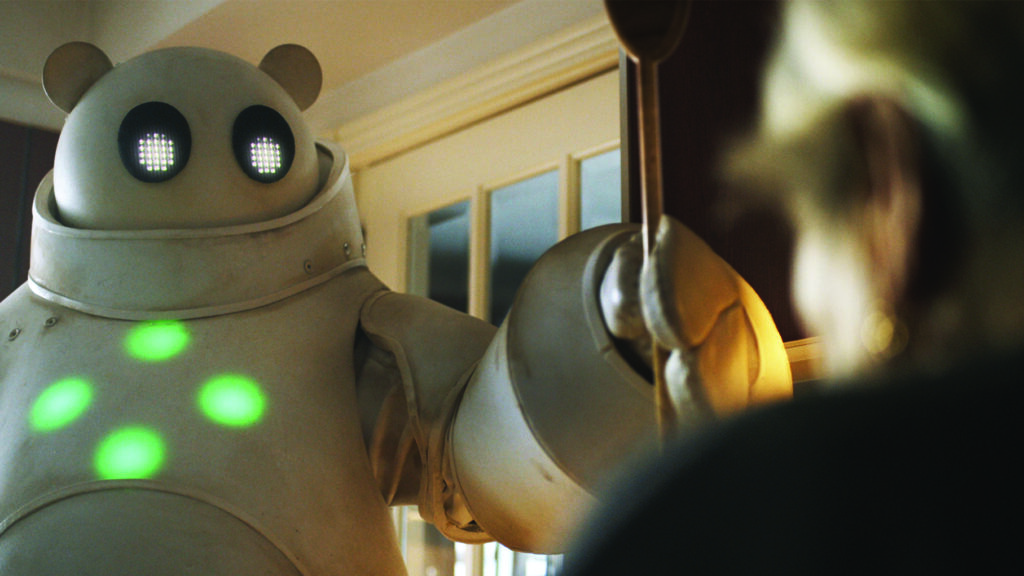

TOTO

Canada, drama; short

Rosa Forlano, a 90-year-old Nonna, teaches a robot how to make spaghetti. Unfortunately, a software update erases her family recipe. TOTO is a sci-fi story about intergenerational communication and the pace of change, both bitter and sweet.