Written by Jacquie Moore, BA’97

My Grade 3 teacher, Mrs. Alexander, read E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web aloud to our class. From the first page, I was hooked — as well as confused and horrified. Why would Fern’s dad want to kill a baby pig? How, exactly, was he going to use the axe? I began to wonder what had happened to my ill-behaved dog who had recently “gone to a farm.” Mrs. Alexander was a terrific reader, and Charlotte’s Web was my favourite part of the day. But I had questions. Alas, afraid to say something foolish, I didn’t share my conjectures about what might be going on in the Averys’ barn.

While context and imagination served up some version of farm life to my eight-year-old urban brain, researchers at the University of Calgary’s Werklund School of Education would have seen lost opportunity in my diligent teacher’s inadvertent short-circuiting of “high-quality conversation.” In her class, as throughout my education, I discovered that there was generally one “right” answer to every question (usually provided by the same one or two students), and I learned to keep my thoughts to myself. I accepted my teachers as primary keepers of knowledge who doled it out according to a strict curriculum.

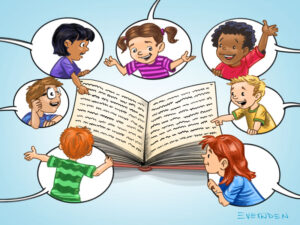

New exploration of literacy learning shows that — if a goal of education is to develop empathetic, engaged citizens capable of democratic dialogue — students must learn from an early age to confidently share their personal experiences and interpretations.

Cultivating a Fertile Field of Ideas

Dr. Maren Aukerman, PhD, is a research professor in Werklund, specializing in curriculum and learning. She is, by nature and profession, an amiable disturber of the status quo. As a high school student in Maryland, Aukerman questioned her teachers about accepted educational practices and policies that didn’t sit right with her.

“I called them out on dress-code requirements and for disciplining a whole class for the infractions of a few,” says Aukerman. Most significantly, the teenaged future researcher was bothered by what she felt was, “the privileging of rote learning over student voice and genuine engagement.” Turning the latter point upside-down would become her passion and form the foundation of her ongoing scholarly research that examines the relationship between talk, child agency and literacy learning among children and their teachers.

Aukerman is particularly interested in how teachers engage with children’s unconventional interpretations of text, and how “meaning-making” can become a more honoured and valued resource within the classroom.

In other words, Aukerman suggests that, had she read Charlotte’s Web to my class, a long, perhaps absurd, wide-open conversation would likely have ensued about, “Wilbur’s worth as a pig, whether Templeton [the rat] was an enemy or ally; whether Wilbur was as good a friend to Charlotte as she was to him, etc.” Divergent commentary, disagreement, idea- swapping and all manner of personal perspective would have been encouraged from everyone in the classroom. Sure, it might have taken many weeks to get through White’s slim novel but, as Aukerman says, “we need to help kids grow up to become democratic citizens who know that ideas matter — their own and everyone else’s.”

Inarguably, creating such pathways for democratic citizenship is a more crucial part of education than ever. According to statistics from the scientific online publication, Our World in Data, global democracy is currently in decline: the number of people that have democratic rights plummeted from 3.9 billion in 2017 to 2.3 billion in 2021. And the outlook for democracy is bleak with political turmoil around the world.

If democracy pivots on citizens taking an active role in the governance of their community and their country, then learning to participate in dialogue, evaluate other people’s evidence and communicate individual ideas is crucial. As Aukerman says, the first step in empowering children to democratic participation is, “for them to believe their voices matter — and they must have things to discuss where divergent ideas can emerge in the first place.”

When the ‘Wrong’ Answer is the Right One

Pedagogy around literacy has come long way even since my standard circa-1980 experience at Acadia Elementary. For example, the Calgary Board of Education’s thoughtful K-12 Literacy Framework includes language and intention that seems to line up with Aukerman’s high watermark for literacy learning:

“Literacy is a lifelong process that is essential to successful learning and living. Diverse literacy opportunities and teaching expertise increase equity for each learner by enabling individuals to reach their full potential, achieve a better quality of life, and contribute to their communities. Literacy is a means to discover and make meaning of an increasingly complex and evolving world. Learners need the confidence and habits of mind to acquire, create, connect and communicate information in a variety of contexts, going beyond the basic skills of reading and writing.”

Alberta Regional Consortia, 2017

Still, Aukerman sees greater opportunity for teachers to facilitate more powerful, high-quality conversation with their young students. In a co-authored chapter in the book, Affect, Embodiment and Place in Critical Literacy (Routledge, 2021), Aukerman writes that, “contemporary literacy education frequently treats children as empty vessels, seeking to fill them up with the right knowledge and strategies.” She sees schools getting too caught up in covering basic skills and guiding students to one “right” answer when reading — sometimes at the expense of children learning to engage in democratic dialogue.

Rather, Aukerman says, kids find deeper meaning and belonging when teachers are empowered to put “interconnectedness” at the heart of literary discussion. Her research, teaching and collaboration with pre-service teachers in Werklund involves guiding her students to structure their future classrooms in such a way that encourages kids to share personal stories, debate and disagree with one another’s perspectives. In that way, she says, “children learn to develop ideas and realize that there are many interpretations beyond their own.”

Aukerman shares an example of how she witnessed a teacher actively invite literary interpretation without instantly correcting or endorsing an answer — and how that approach successfully stoked participation, creativity and critical thinking. Rather than explain to a Grade 5 student that he misunderstood the word “beast” as a “very mean animal” in a fable about a donkey, the teacher invited conversation by encouraging students to lean on their own reasoning and experiences to interpret the word’s meaning in the story. Left to sort it out with classmates, the boy, Aukerman says, didn’t infer that his answer was not what the teacher wanted, and yet was pushed to better justify his interpretation.

Through conversation, the students were driven to seek evidence for their own ideas that they then could modify or strengthen. Providing such a safe, widely engaging space, says Aukerman, “changes the quality of education from passive facts being absorbed, to a structure that lays the groundwork for kids to become democratic citizens.”

Tell Me More!

Michelle Bence Mathezer is a doctoral candidate in Werklund who has worked and published with Aukerman. Her dissertation focuses on data from teacher read-alouds and dialogue in kindergarten classrooms. Like Aukerman, Bence Mathezer’s research explores reading as a powerful place for kids to learn how to think, collaborate and develop critical analysis skills needed for success in the 21st century. As a seasoned literary coach and, currently, a weekly volunteer in a rural kindergarten classroom, Bence Mathezer has seen how students learn to keep idiosyncratic ideas to themselves.

“When you ask a kindergarten classroom to share their ideas at the beginning of the year, they all participate,” says Bence Mathezer, BMus’94, BSc’95, BEd’99, MA’18. “But, when you ask questions later in the year or into grades 3 or 5, you get the same couple of kids giving standard answers.” She says that’s because kids quickly “learn the signals for the ‘right’ answer that the teacher wants — they learn to get on the same page as the teacher, and that inadvertently shuts down alternate ideas.”

Bence Mathezer’s current research looks at what happens when “we create a scenario in the classroom where we have lots of different ideas coming out and then we allow everyone to react to one another’s contribution.” She explores how tight interpretations of literature and short interactions restrict diverse ideas and conversation. “The idea is that we want to construct personal meaning and get a deeper understanding of things by having to clarify and elaborate on ideas with others,” she says.

Creating deeper dialogic discussion in classrooms may require only a small shift in how many teachers already operate in the classroom. “The key is changing our intention as teachers,” says Bence Mathezer. “We can ask the same questions when reading to students but, by dropping our expectation of a single right answer, we immediately open the space up to many ideas.”

By her own description, Bence Mathezer is, “a white, female, middle-aged teacher.” She constantly examines her own lens on what she’s reading aloud to a group of kindergarteners. “I’m not sure my interpretation of a text will resonate with a young student from another country who has had experiences that are different from mine,” she says. “She might understand the text, but in a very different way from me.” Bence Mathezer says inviting personal experience and opinion changes the way teachers think about knowledge. “By following up an answer with, ‘Interesting! Why do you think that? Tell me more!’ teachers develop a shared interpretive authority with students,” she says.

Opening the floor to students and their stories may seem like a small thing, but Aukerman and Bence Mathezer say that kids learning to drop the assumption that knowledge lives in the text is a big step toward developing a world of confident democratic citizens. Reading to empower open conversation and swap ideas is the knowledge, they say.

In other words, kids know.

Sometimes, we just need to get out of their way.