Written by Jacquie Moore, BA ‘97

Hiding among the shaggy stems of sorghum and banana plantation on the perimeter of a neighbour’s house, 27-year-old Régine Uwibereyeho King makes a promise to God: if she lives — that is, if she is not discovered and murdered — she will devote her life to helping others get through the terror and grief of the mass-slaughter happening all around her and tell the world what she had witnessed.

Now an associate professor in the University of Calgary’s Faculty of Social Work, Dr. King, PhD, is making good on that promise.

Over the course of 100 terrible days in the spring of 1994, more than 800,000 Rwandans were murdered while the rest of world looked on, largely unwilling to help. Urged on by extremists determined to ethnically “cleanse” the country of its minority group, Hutu civilians systematically killed their Tutsi friends and neighbours, looted their homes, and destroyed any evidence of their identity.

Of all the indelible marks the genocide made on King — who spent those three months in hiding with her family, listening to death-chants and enduring the murders of two of her brothers — it’s the courage and compassion she witnessed that has most deeply impacted her life.

“We were helped by a few neighbours we never expected would take that kind of risk for us,” recalls King. Two young people who had attended meetings of the militia came to warn King and her family about when attacks were going to happen and where. While the family was in hiding, a female neighbour cooked food, prepared drinks and brought them to the bushes without revealing their location. Another neighbour and his family agreed to hide them when they ran to his house. Yet another neighbour risked his life by returning the family’s milking cow that had been looted.

Their bravery inspired King to strengthen her own compassion in others as a path to expanding peace in the world.

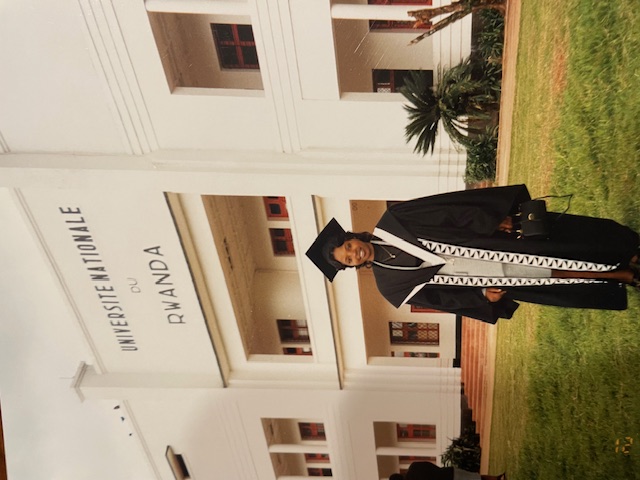

King was an undergraduate student at the National University of Rwanda and had returned to her parental home in the south of Rwanda when the genocide began. Once it was over, she spent a year searching for a way back into her altered life and helping her mother settle into taking care of King’s four remaining siblings, as well as nurturing several orphaned children who moved in with them, in their almost ruined home.

Photograph courtesy of Régine King.

Emotionally and psychologically wounded as she was, King says she was acutely aware of her fortune to be “among the very few Tutsi who survived the genocide with a mother and some siblings, and an almost-completed university degree.” Her family gave her a reason to live; her education provided a basis from which to support others and to grow professionally and intellectually. For King, “nothing in life should be taken for granted.”

King managed to finish her degree at the National University and, true to her promise, pursued work that allowed her to help others who were suffering the aftermath of the genocide. In her role within a psychosocial program at World Vision, King participated in a series of healing workshops that changed her life.

“I processed my own grief as I learned about bereavement and the importance of dealing with emotions and forgiveness,” she says. “I also learned how to listen to the stories of the wounded.”

Contrary to the adage that time heals all wounds, King has said that, when it comes to emotional wounds inflicted by genocide, time is not enough. In a recent article published by the American Psychological Association, she writes that “people whose world has been turned upside down (by genocide) need safe spaces in which they can share their personal and collective experiences, develop new understandings of their suffering, and cultivate compassion and mutual support … to move forward.”

The shared experiences, mutual compassion and commitment born out of the various workshops she facilitated convinced King that “healing and forgiveness are possible, and compassion for others can be a unifying resource to prevent and overcome some of the psychological impacts of violence.”

King moved to Canada in 2000, where she earned both a Master of Education in counselling psychology and, ultimately, a PhD in social work from the University of Toronto.

King has been a witness of psychosocial transformation both through her frontline work and her research that, for the last decade, has been focused on healing approaches from genocide and other forms of structural violence, and other mechanisms that people mobilize to overcome adversity. In Rwanda, she explored the power of the shared experience of storytelling and the devotion of Rwandans who had managed to forgive and/or receive forgiveness, and who work tirelessly to help others. She has recently expanded her research on homegrown solutions — a framework that draws on traditional Rwandan values and practices to tackle socio-economic problems through various programs and is currently exploring approaches to racial justice at the University of Calgary.

This year, King will also be documenting the stories of Rwandan genocide survivors now living in Calgary, while also writing her memoir.

“There is healing in sharing stories of suffering,” she says. “Telling the world what happened — that’s how we can work toward ensuring such atrocities don’t happen again.”

“People here might think genocide could only happen in some other place, that it has nothing to do with them, but violence is everyone’s business.”

Violence has taken, and continues to take place on Canadian soil, says King. “We just need to open our eyes and hearts to see and feel it. Rather than feeling sorry for the past, we should be concerned with the current genocides, and remain true to ‘never again,’” she says.

Despite her strength and optimism, King admits her heart is aching as she watches what’s happening in the Middle East, Sudan, and Democratic Republic of Congo. “That is everyone’s business — it isn’t just happening ‘over there,’” she says. “Power, greed, and fear are prone to violence, and it can happen anywhere, even in our homes.”

King believes that peace comes when we begin see ourselves in others, as part of a shared humanity living in a shared world.

“By telling and listening to stories of any kind of violence from anywhere in the world, we can long say we did not know. The stories of suffering call for compassion and empathy for others; they also call for responsibility,” she says. “I don’t tell my story to make you sad — I tell you so that it doesn’t happen to anyone else. I tell you my story, so that you can become the ambassadors of peace.”