The thing about space researchers is that they kinda don’t care what is impossible. The impossible is really just a challenge to build a better tool, collect more data or find another approach.

That’s the kind of space research and development that has been happening at the University of Calgary since 1960 (when it was still a satellite campus of the University of Alberta) when it took possession of the Sulphur Mountain Cosmic Ray Research Station west of Canmore. The facility (which was dismantled in the early 1980s) was part of a worldwide network trying to understand energy outside of our solar system. It was the early days of research into the aurora and collecting data from the top of the mountain was crucial. Fast-forward ever so slightly to 1972 when UCalgary helped capture the first global auroral images from space.

Now, UCalgary leads the development and operation of the world’s most extensive network of ground-based instruments for observing the aurora. It also collaborates with the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), European Space Agency (ESA) and NASA. UCalgary has sent equipment up on more than 20 space missions that, among other discoveries, were at the forefront of advancing telecommunications and global positioning systems. And that’s just the Faculty of Science. The Schulich School of Engineering is developing rocket fuel and researchers in Kinesiology, Arts, and Cumming School of Medicine are using health to better understand everything from bone loss to how the brain responds in space.

It’s all being done by a bunch of space researchers who are building equipment, operating infrastructure, untangling data, sharing that data and coming up with the next way to push what is possible is space research.

All aboard a risky satellite mission

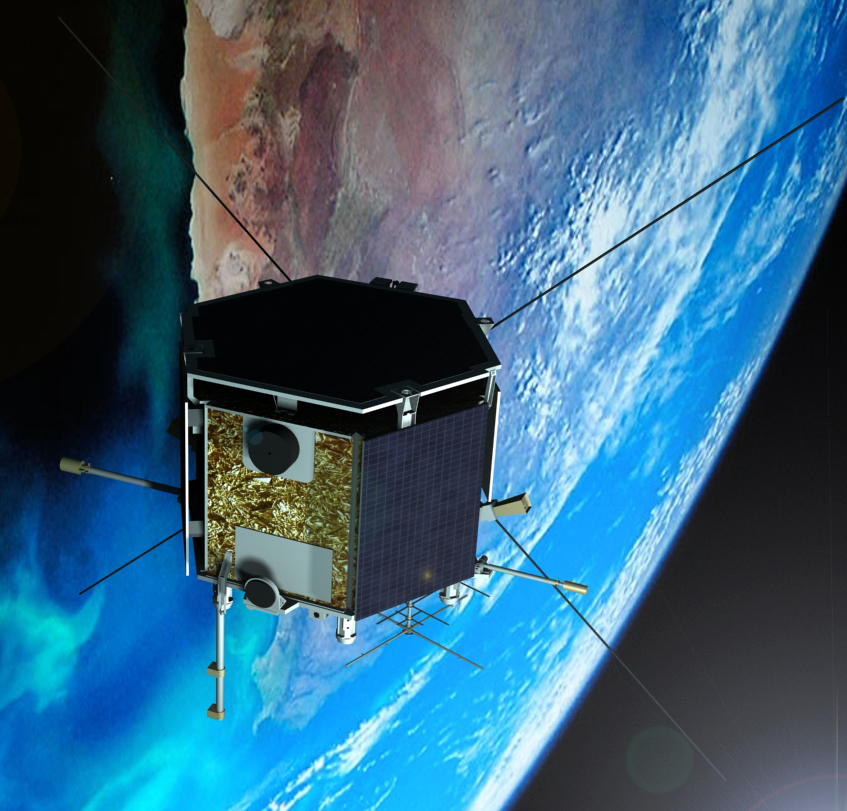

In 2013, a collection of one-of-a kind instruments was launched into space. Those instruments — collectively called Enhanced Polar Outflow Probe (e-POP) — were on board the CASSIOPE satellite and UCalgary was in charge of overseeing them.

It took more than a decade of research, planning, building, and the collaborative efforts of universities, industry across Canada and CSA. If CASSIOPE (Cascade, Smallsat and Ionospheric Polar Explorer) made it into orbit, the mission was expected to last six months.

“We knew it was risky going in because we were doing something that no one else had done before,” says UCalgary Physics and Astronomy professor Dr. Andrew Yau, PhD, a mission scientist and project lead involved from the beginning.

Nearly 10 years later, CASSIOPE and the e-POP instruments are still circling the Earth. UCalgary continues to operate the instruments and the mission has been part of the ESA’s Swarm satellite constellation and known as Swarm-E since 2018. It has the potential to collect data for another decade before burning up in the atmosphere.

The eight e-POP instruments were designed, built, and operated by UCalgary and its e-POP partners. They include auroral imagers, particle sensors, radio wave and GPS receivers, and more to help understand the structure and dynamics of the plasma in the Earth’s upper atmosphere. It’s looking at space weather that can affect systems on the ground, including power grids and navigation systems.

The way the satellite orbits the Earth is unique; it has an elliptical, rather than circular orbit. The satellite dips down as low as 325 kilometres above the surface of the Earth and up to 1,500 kilometres, collecting measurements other satellites in circular orbits can’t.

As the satellite continues its 14 daily loops around the Earth, on the ground, UCalgary’s “cradle-to-grave” involvement in the project has created a team with broad experience that is rare for a Canadian university.

“We’ve been able to train people through every aspect of this spacecraft’s life cycle, starting from the design through build, test, launch and operations,” says e-POP project manager Andrew Howarth, BSc’03, MSc’06. “It’s a unique opportunity to be involved in every one of those aspects.”

That holistic expertise has UCalgary poised for future space missions.

The aurora like it’s never been observed before

The images of swirling colours in the night sky are spectacular, but the northern lights northern aren’t just a pretty postcard picture. They also pack a punch with science.

The aurora comes from the Earth’s space environment, a region around our planet that blends seamlessly into our atmosphere and extends hundreds of thousands of kilometres into space. The space environment contains vast populations of charged particles that (when they hurl towards our atmosphere) can give us a great light show and impact things like electrical grids and satellite navigation systems, as well as radio and satellite communications. While you may not have checked seeing the northern lights off your bucket list, rest assured what is happening in the aurora impacts your everyday life.

UCalgary’s Auroral Imaging Group (AIG) developed and operates the world’s most extensive network of ground-based instruments for observing the aurora borealis. It includes field stations across the Canadian North that are decked out with instruments that have been designed, built and maintained by UCalgary. All of that feeds Canadian research as well as partnerships with international space agencies and thousands of citizen-scientists.

It also creates one heck of a camera roll. AIG projects have so far generated more than 1 billion images that will be on AIG’s AuroraX. When it launches, it will be the first data platform for auroral science. Data from instruments and cameras will be openly available and accessible through tools that make it easier to navigate so past, present and future auroral information can be used for ongoing research of the magnetosphere.

This brings us a long way from when UCalgary imagers captured the first image of the aurora from space in 1972 and opens the door for more beautiful science in the future.

AuroraMAX

It’s not quite the same as being there in person, but it’s still pretty cool. From September to April, the AuroraMAX observatory offers a live online feed of the sky above Yellowknife, N.W.T. Not every night offers a sure-fire spectacular light show, but you can still tune in from your computer to see for yourself. Movie replays of previous nights are also available. Like this one from Jan. 2, 2022.

AuroraMAX is a collaborative initiative between UCalgary, the City of Yellowknife, Astronomy North and the CSA.

The workshop where things are made

They make things, fix things and break things. The latter is to be expected when the things you make are new inventions that push the boundaries of manufacturing and are literally being sent out of this world.

They are a team of technicians in UCalgary’s Science Workshop. Their job is to work with researchers in the Faculty of Science to develop physical products used to help execute their research.

Some of the Workshop’s creations are orbiting the Earth on UCalgary-operated satellite missions. Other objects have been shot up into the atmosphere on low-orbit rockets. Still more are part of the Aurora Imaging Group’s network of instruments spread across the Canadian North. The shop has made grape-sized domes to help track space weather and built telescopes for the Rothney Astrophysical Observatory.

“If you can buy it off the shelf or from another manufacturer, we can modify it, too,” says Science Workshop Team Lead Todd Willis.

The Workshop dates back to the 1960s, around the time space research at UCalgary was emerging. It was revamped in the 1990s and renovated and expanded in 2018. Now the Workshop has full design and Finite Element Analysis capabilities, 3D printing in plastics and metal, five-axis CNC milling/lathe machines, and many fabrication tools. Advanced software is used to help design and stress-test the products before they are built. In the Workshop, measurements are sometimes done in microns (one ten-thousandth of a millimetre), and products are made out of materials like Kapton film and oxygen-free copper.

The Workshop creates hundreds of items each year. Space objects have been a mainstay from the beginning and now areas including robotics and quantum technology are using the Workshop for help exploring untapped territory.

It’s that kind of challenge that motivates the team of technicians.

“We’re driven by pushing our boundaries,” says Willis. “Professional race-car drivers are the best because they push to the very limit of what is possible. That’s what we do. Requests come in that we don’t think are possible, but we figure it out.”

Five decades of stargazing at the Rothney Astrophysical Observatory

Head toward the dark skies just south of Calgary and you’ll find this observatory run by the Faculty of Science. Elementary school kids, undergraduate students, international astronomers and the curious public have been accessing its expert staff and seriously impressive telescopes to get a closer look at the night sky for half a century.

Cheaper, greener, safer rocket fuel

You can grumble about the price of fuel, but imagine being NASA, with an Olympic swimming pool-sized tank to fill.

In fact, the 2.7 million-litre fuel load needed to carry the Artemis I mission to the Moon and back is slightly larger than a typical competition-sized pool, but it shows the need to carry vast volumes of expensive, volatile liquid fuel remains a massive headache for space rocket designers.

That’s why researchers at UCalgary are focused on powering the race to space with something cheaper, greener and safer, in the form of solid rocket fuel fashioned from paraffin wax and nitrous oxide.

“The fuel we are using is a lot safer for the environment than many of the toxic fuels used in rocket motors,” says Dr. Craig Johansen, PhD, associate professor of mechanical engineering at the Schulich School of Engineering.

“Paraffin wax is used for candles. Nitrous oxide is a widely used anesthetic for medical procedures,” he says. “You take these two really common materials, put them together in a rocket motor and it’s something a lot safer to launch and safer for the environment.”

Solid fuel and hybrid rocket technology is a key part of the rocket research taking place at UCalgary through the Aerospace and Compressible Flow Research (AERO-CORE) Group.

The group also researches hypersonic atmospheric entry aerodynamics; hybrid rocket engine performance assessment using plume luminosity oscillations; and experimental investigation of self-pressurising propellant injection into a rocket motor combustor.

It really is rocket science – and UCalgary’s rocket testing facility is located at the Rothney Astrophysical Observatory.

UCalgary also boasts an undergraduate student group (Student Organization for Aerospace Research) that competes in a rocket competition.

Access to that fancy new telescope to figure out the past, present and future of the universe

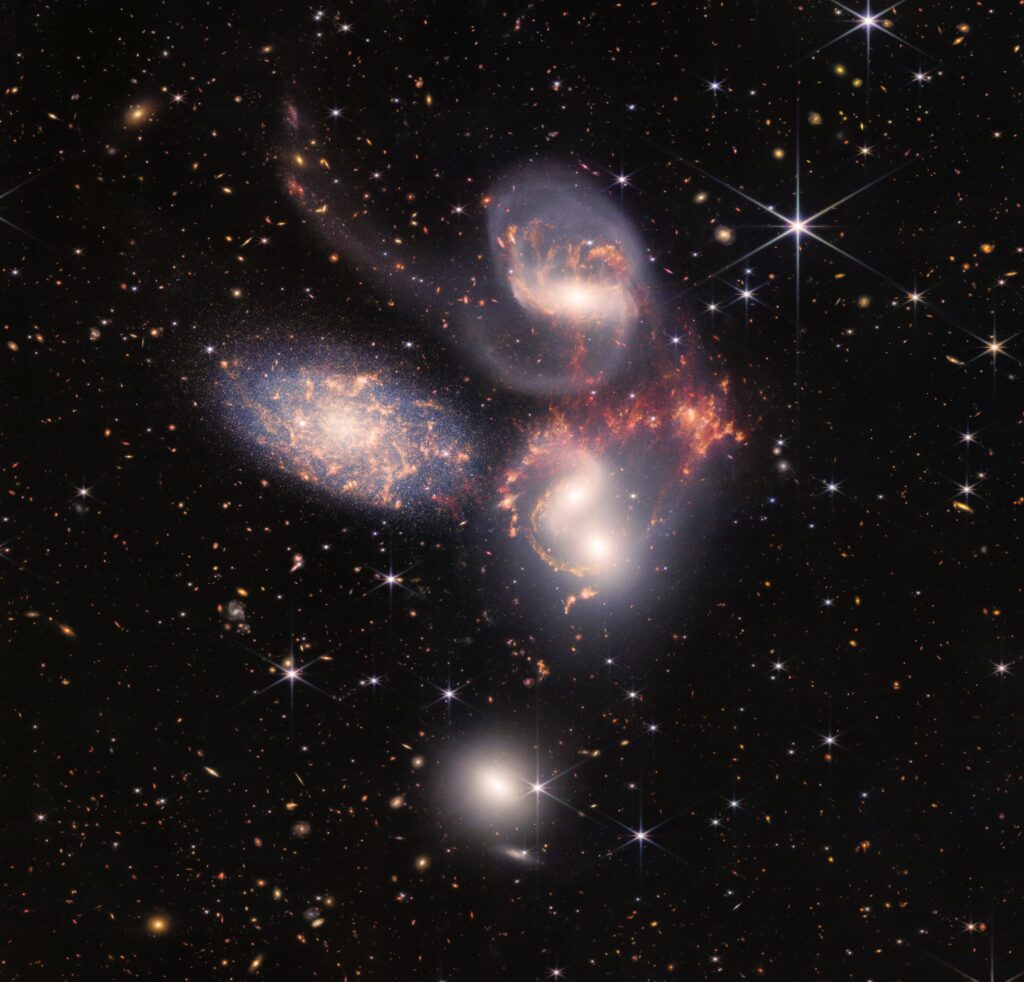

When the first images from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) were shared around the world, even the most casual space enthusiast knew they were spectacular. Scientists knew it was just the beginning. JWST is going to crack open major scientific discoveries.

The telescope can look through dust and clouds and peer through 13 billion years of cosmic history to see the birth of stars and galaxies. The successor to the revolutionary Hubble Space Telescope is the most powerful observatory launched into space and that gets astronomer Dr. Matthew Taylor, PhD, excited.

Taylor, an assistant professor in UCalgary’s Department of Physics and Astronomy, researches the smallest galaxies in the universe and the black holes that may reside in their centres.

As a partner in the mission, CSA gets 300 hours of observing time in JWST’s first year. After a lengthy proposal process that included pitching the scientific questions Taylor wants to ask, how he will go about looking for answers and why it is important, the CSA allotted him an impressive 40 hours of this telescope time. Taylor’s first observing window was in December 2022 and then again in Spring 2023. He has 18 targets that he is hoping to achieve in that time.

For one thing, Taylor is looking for “intermediate” black holes.

“Black holes heavily influence the evolution of a giant galaxy, so it’s important for us to understand how they form,” explains Taylor. “We know they form early in the universe, but exactly how they form and how they grow to such huge sizes is still a bit uncertain.”

The more we learn about these black holes, the closer we get to understanding how the universe started, where it is now and what the future could hold. Those are big questions and, along the way, there are bound to be a few magical moments.

“When you get brand-new data, there is a moment when you know that you are looking at something that no one in human history has seen before,” says Taylor. “Those moments are few and far between, but, when they happen, it’s a reminder of why this job is so exciting.”

Space-health research to help both astronauts and those of us on Earth

UCalgary is quickly establishing itself as a national hub for space-health research.

With research taking place on everything from bone loss to how the brain responds to spaceflight, UCalgary researchers are impacting how future astronauts will survive in space, while using the same science to improve life here on Earth.

“We can learn a lot about health on Earth through space research, and I can take a particular example, where I study bone and with astronauts, things happen over six months in space that would take a decade on Earth,” says Dr. Steven Boyd, MSc’97, PhD’01, director of the McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health and a professor in the Cumming School of Medicine.

“Space accelerates our understanding of health on Earth.”

In November 2022, UCalgary hosted the first-ever Canadian Space Health Symposium. Leading national and international scientists investigating the effects of spaceflight on human health gathered to share ideas, along with those whose research has the potential to make a significant contribution to space-health.

The ideas and research shared in Calgary may someday be helping humans survive on Mars and beyond, but the knowledge is also invaluable for those living on Earth, says event organizer and session chair Dr. Giuseppe Iaria, PhD.

“Very few people go to outer space, so why do we do this? Because it can help people here on Earth, and what we learn on Earth can then help Astronauts, as well. As an example, learning how to be effective in health-care delivery in remote and isolated locations on Earth is definitely going to help how we will deliver health care while travelling to Mars,” says Iaria, director of NeuroLab and professor of cognitive neuroscience in the Department of Psychology.

“There is so much we can learn on Earth that can be applied to space travel, and the other way around.”