Written by Jacquie Moore, BA’97

Dr. Dawn Kingston, PhD, wants to change how we perceive, diagnose, and treat pregnant and postpartum women with emotional health issues — in fact, she’s calling for a paradigm shift.

For instance, she says, the widespread assumption that postpartum depression (PPD) is an unequivocally unpredictable illness hinders sensitivity to and screening for signs that are often present — and treatable — long before a baby is born.

“There’s a myth that PPD usually just hits women out of the blue,” says Kingston. In fact, “the biggest risk factor in postpartum depression is prenatal depression and anxiety.”

A researcher and professor in the Faculty of Nursing, Kingston is striving to improve perinatal mental health care — perinatal being the period from conception until 12 months after delivery of the baby — by developing and evaluating approaches for screening and treating women who struggle with negative mental health during and pre-pregnancy. Given that a baby’s prenatal (i.e., pre-birth) experience can frame the well-being of the child going forward into adulthood, the value of such a paradigm shift is immeasurable.

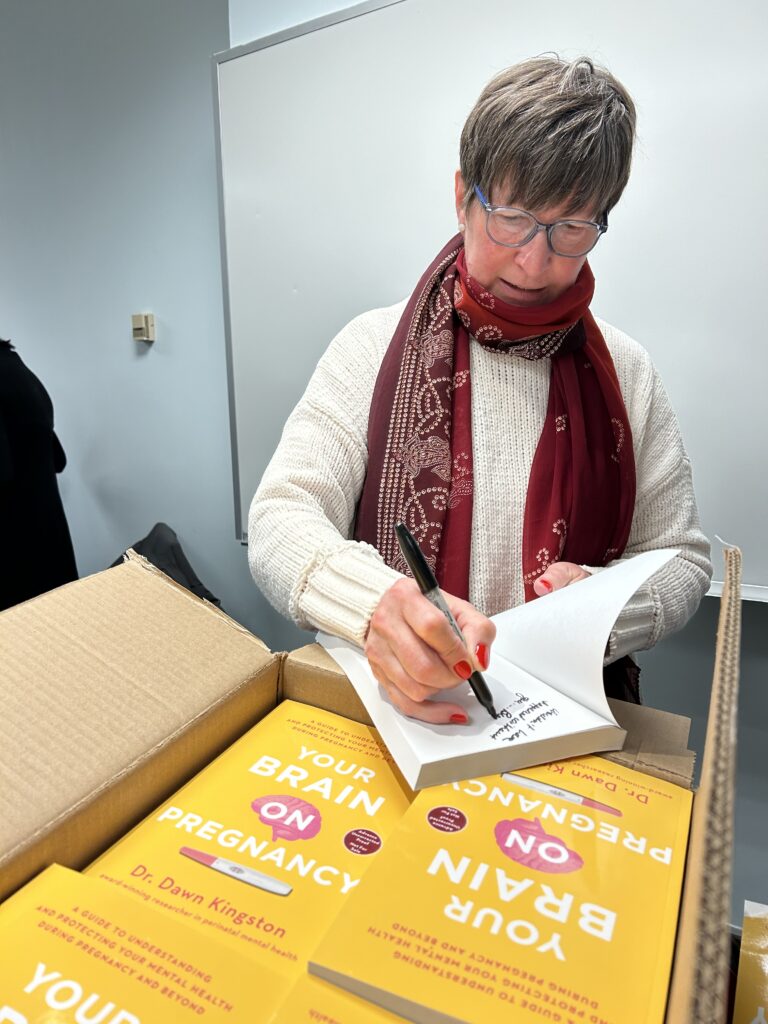

In her groundbreaking new book, Your Brain on Pregnancy (Simon & Schuster; scheduled for publication in September 2024), Kingston takes to task a belief that hormonal changes are the main cause of depression, anxiety and toxic stress, and shares strategies for how expecting parents can better manage or reverse negative emotional health for mothers and their children.

Motherhood and Mental-Health Myths

Over the course of her 25 years working with women and babies as a registered nurse and health researcher, Kingston has learned that as many as one in four pregnant women struggle with their mental health.

One of the most widely known mental-health issues, PPD is a condition that affects more than 20 per cent of women after pregnancy. In contrast to the so-called “baby blues,” which begin within the first three or four days of giving birth, PPD is a deeper depression that often lasts much longer. It usually starts within the first month after childbirth (although it can occur any time within the first year) and can last weeks to months. In more serious cases, it can develop into chronic episodes of depression. PPD is characterized by symptoms that include sadness, irritability, difficulty bonding with one’s baby, insomnia, loss of appetite, and, in rare cases, even infanticide.

As for before the birth, “a big myth around anxiety and depression during pregnancy is that it has to do with hormones,” says Kingston. “Women don’t always recognize the symptoms and, therefore, do not seek help, because they think it’s something that comes with pregnancy or being postpartum.”

While PPD is a real and serious issue, Kingston says that depression during pregnancy is lesser-known, but just as harmful, if not more so. Without treatment, depression and anxiety symptoms can continue after the child is born, impacting a mother’s long-term health, as well as the baby’s development. With three decades of research on the effects of prenatal stress, depression and anxiety, it’s clear that a baby’s brain and nervous system can be wired so that the child is more vulnerable to mental health and development challenges.

A New Conversation

If hormones aren’t solely to blame for postpartum women feeling overwhelmed, anxious or depressed, what is?

The most common cause of PPD is prenatal anxiety and depression. “The statistics are high on that: up to 80 per cent of women with postpartum depression recall signs of anxiety or depression during pregnancy,” says Kingston, adding that anxiety and depression can be measured on a continuum. “Many women may be experiencing some negative mental-health symptoms long before they become pregnant.”

She says that many women who are diagnosed with PPD went into their pregnancy with an unhealthy level of stress, depression or anxiety.

“Maybe they’ve had a hard life; maybe they haven’t felt safe; maybe they have low social support, a difficult relationship or previous mental health problems,” says Kingston. Those factors, she explains, can lead to a dysregulated nervous system before, during and after pregnancy.

What Needs to Change?

Rather than a system that siloes women’s mental health and pours most of its resources into postpartum mental health, Kingston says research shows a need for emphasis on helping reset women’s nervous systems.

“In a routine pregnancy, most women have up to 13 check-ins with a health-care provider,” she says. In most cases, none of those visits include screening for depression and anxiety. “Certainly, there are small pockets of health-care provision that include that kind of testing but, as a system, we are not doing that.”

It’s understandable that physicians may be reluctant to question a pregnant woman about her mental health because, as Kingston puts it, “it can be like opening a Pandora’s box” of problems they don’t have time or resources to address. In addition, if they were to refer a patient for therapy, waitlists are often months-long. It’s by default, then, that the first line of treatment is often a prescription for anti-depressants. While those can be safe, many women don’t feel comfortable taking medications during pregnancy — and so the cycle of not getting help continues.

“It doesn’t have to be that way,” says Kingston.

Getting the Brain Ready for Pregnancy

Kingston says the key to a healthier future for women, babies and families is to, “marry cutting-edge neuroscience and women’s emotional health.” Given that a mother’s brain wires a baby’s brain, she says, “our health-care system must focus on testing and using interventions that come from a brain-based perspective,” rather than a mental-illness perspective.

“A dysregulated nervous system is at the root of stress, anxiety, depression — and that doesn’t have to be permanent. There are evidence-based neuroscientific treatments that can reset the nervous system that have not been brought into the perinatal world.”

Non-invasive, brain-based therapies, says Kingston, “can be first-line treatments to rewire mother and baby brains.” Such evidence-based therapies include neurofeedback and vibracoustic stimulation.

Neurofeedback, Kingston says, “can help reset unhealthy brain signals” by providing feedback from a computer-based program that assesses brainwave activity. Through this process, the brain can learn to regulate and improve its function. Kingston also points to vibracoustic stimulation (the application of specific acoustic frequencies through headphones) as a non-invasive means of potentially “rewiring specific symptoms of the (fetal) brain.”

These cutting-edge treatments are, says Kingston, “easy, inexpensive and lasting.” That, she adds, “is where I see hope for the future of perinatal mental health.”

Empowering Self-Care

Kingston and her team are also striving to empower women to manage their own emotional health, even without engaging in treatments.

“There are many things women can do at home to help reduce anxiety and stress,” she says. “When we get overactivated by, say, an argument with a partner, we can learn to be aware of where we are at with our brain and our nervous system, and to address that.”

The goal of brain-based work is that we learn to be flexible, says Kingston. “We may feel hopeless. Sometimes we can learn to get back up to the space of calm and regulation — good mental health, perinatal or not, is learning to self-regulate our brain and nervous system,” she says.

Kingston suggests a couple of specific home-based therapies that can be effective for women throughout pregnancy. Simply taking a few deep breaths puts pressure on the vagus nerve, which communicates to the brain and body that things are safe and helps regulate the nervous system. Tapping on specific body parts where the vagus nerve travels is highly effective. As well, listening to music at specific frequencies (such as harp music) causes the eardrum to vibrate at that certain frequency, again stimulating the vagus nerve and creating calm. “Research shows us that harp music has a very specific frequency that calms us,” says Kingston, who recommends music by nurse and harpist Steve Rees.

Hope Abounds

As the paradigm shifts, Kingston and her team continue to lead the field in perinatal mental health using e-technology for screening and therapy so that women can get help whenever they need it, wherever they are.

The highly accessible Hope platform provides free online, science-based screening, tools and therapies to support emotional well-being for women in the areas of pregnancy, postpartum, relationship, menopause, and grief and loss. “If you’re sad, exhausted, or feel like you don’t care anymore, there’s a way to reset, there are resources and there’s hope,” says Kingston.