Written by Jacquie Moore, BA ’97

There was a time when a particular elm tree — planted in the early 1900s at the intersection of four backyards in Calgary’s Victoria Park — was doubtless the focus of play for neighbourhood kids who swung from its branches and took shady respite under its leaves.

Today, the tree sits, lonely and inconvenient, in the middle of Parking Lot No. 14, north of the Saddledome. Known as the Stampede Elm, its future currently hangs in the balance as the City of Calgary looks to move ahead with redevelopment of lands adjacent to the Stampede Grounds.

So what? Isn’t it just a run-of-the-mill tree — not even that old by tree standards — that has outlived its usefulness and beauty? On the contrary, the elm is deeply meaningful to historians, arborists, storytellers, environmentalists, educators and nostalgic Calgarians for whom the tree’s impending demise represents a lost opportunity to better know this place and its people.

Dr. Peter Dawson, PhD’98, is a professor in the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology whose research focuses on using reality-capture technologies to digitally preserve heritage at risk. He collaborates with community members, as well as students and other faculties, to scan and print 3D iterations of buildings, geological formations and, yes, even a tree, to make lasting records of tactile and poignant learning tools for future generations.

Most recently, much of Dawson’s work has been in partnership with Indigenous Knowledge Keepers in helping preserve the physical memory of a dark chapter in our history.

In 2019, Dawson met Angie Ayoungman; Gwen Bear Chief; Dr. Vivian Ayoungman, BEd’70, EdD; and Herman Yellow Old Woman at a workshop he organized around finding ways to commemorate and preserve the few remaining Indian Residential School buildings in Alberta. As children, all four of them had attended Old Sun, a residential school that operated on the Siksika Nation from 1931 to 1971.

The school, which now serves as a First Nations community college, still holds an imposing place on the landscape near Gleichen. Surprisingly perhaps, given the trauma and cultural genocide that took place inside, Angie, Vivian, Bear Chief and Yellow Old Woman would prefer to see the school remembered, rather than demolished.

“The members of this group, along with other former students/survivors, feel strongly that these buildings need to be preserved because they are witnesses to history and sites of conscience that refute residential school denialism,” says Dawson. His digital heritage research group used laser scanners to rapidly capture the architecture of the building, and its interior and exterior measurements, while the Knowledge Keepers recalled various descriptive details of the building’s appearance that had changed over the decades.

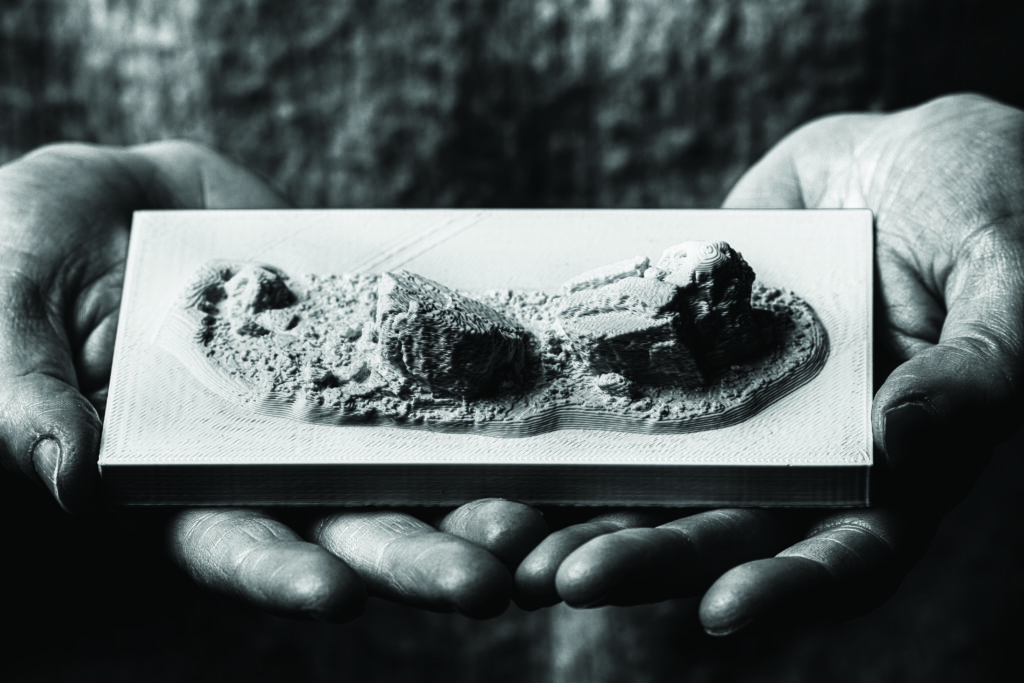

The resulting digital data was used to create a virtual visualization of the school and — with the help of research associate Dr. Katayoon Etemad, MSc’10, PhD’15, in the Department of Computer Science — an uncannily detailed 3D print. The data also informs a complete set of “as-built” architectural plans that will help ensure Old Sun can be maintained, repaired or rebuilt if the Nation decides.

Perhaps most significantly, the manifestation of Old Sun as a small 3D print contains a unique element of healing. Bear Chief says that, when she held the model, she “felt like our stories of residential schools and what they did to us will not be swept under the rug.”

Dawson will continue to work alongside the Knowledge Keepers to explore how virtual and physical models of Old Sun and other former Indian residential school sites “can be used to inform the public about a chapter in Canadian history that caused great harm and suffering to generations of Indigenous people.”

For Angie Ayoungman, the project has provided some peace of mind. “Here is this big stone building that I had to go to when I was a child,” she says. “It’s remarkable that I can now hold it in my hands. I can point to a room and tell my story.” This opportunity, she says, “will help to make sure my experiences are never forgotten.”

Old Sun

Located on the Blackfoot Reserve near Gleichen, Old Sun was one of 130 residential schools across Canada. Among the 25 that existed in Alberta, the Old Sun building represents intergenerational trauma among Indigenous Peoples; its digital capture will serve a role in education for all ages.

The Okotoks Erratic

An important historical site of spiritual significance to the Blackfoot peoples, the “big rock” is also a popular tourist destination. Routine digital scanning helps demonstrate how the 16,000-tonne boulder is affected by visitors who attempt to touch or climb it.

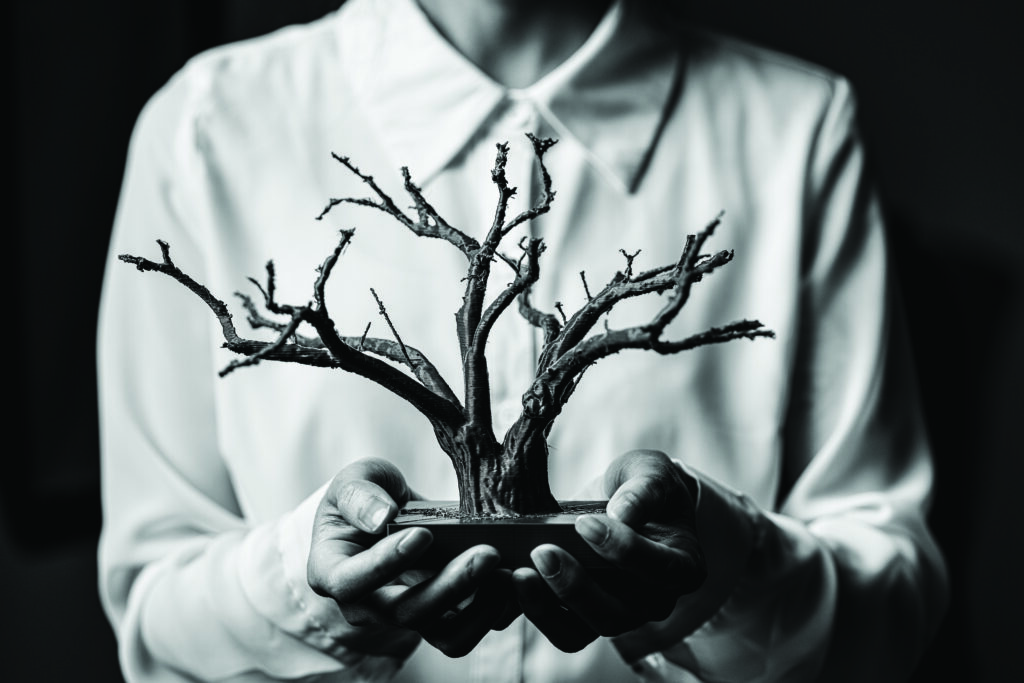

The Stampede Elm

The City of Calgary had hoped to relocate the more-than-a-century-old tree with the help of an expert transplanting service. Unfortunately, one of its main branches is damaged, so the elm can’t be moved. The City worked with UCalgary’s Anthropology and Archaeology department to document the tree, making it the first biological heritage item captured with its scanning technology.

Explore more heritage sites, including, interactive 3D models at the University of Calgary’s Digitally Preserving Alberta’s Diverse Cultural Heritage Project.